We know the “really big one” is coming. But what exactly is going to happen to cities along the Pacific Northwest coast?

As the largest earthquake since 2001 hit Seattle area on July 12, 2019 and earthquakes hammer the Southern California desert, I thought the risks of a tsunami-related earthquakes were worth revisiting.

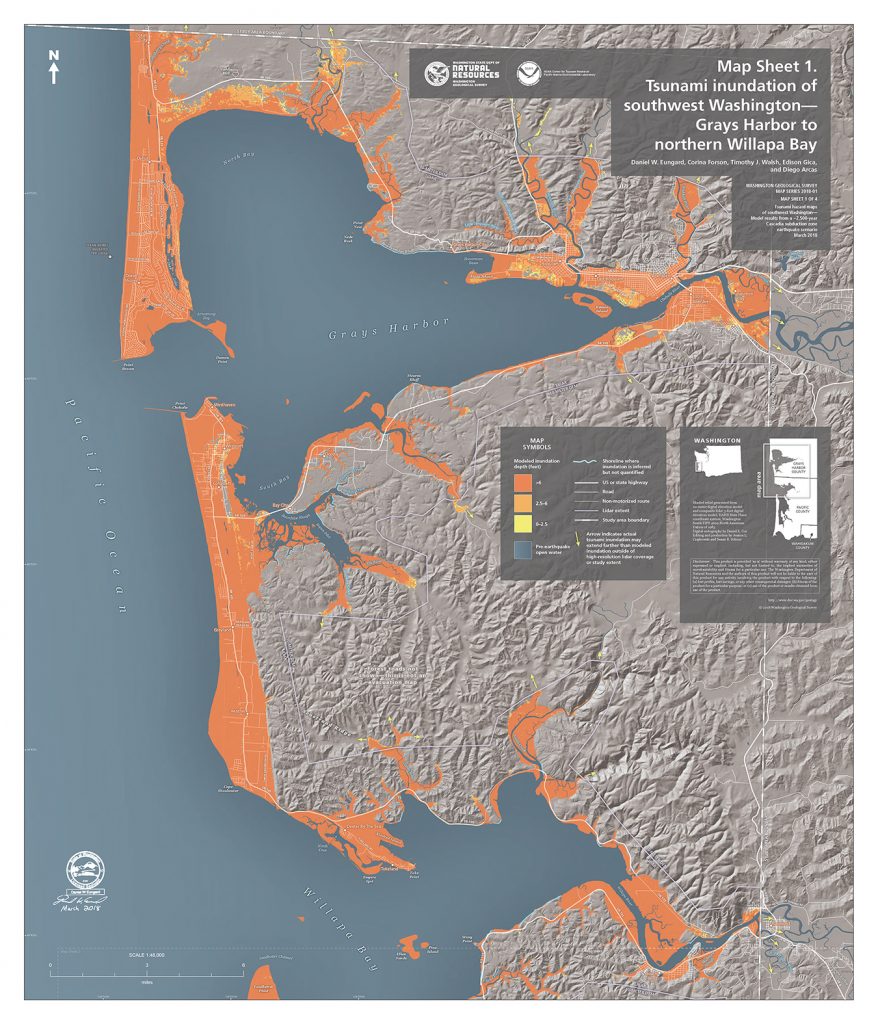

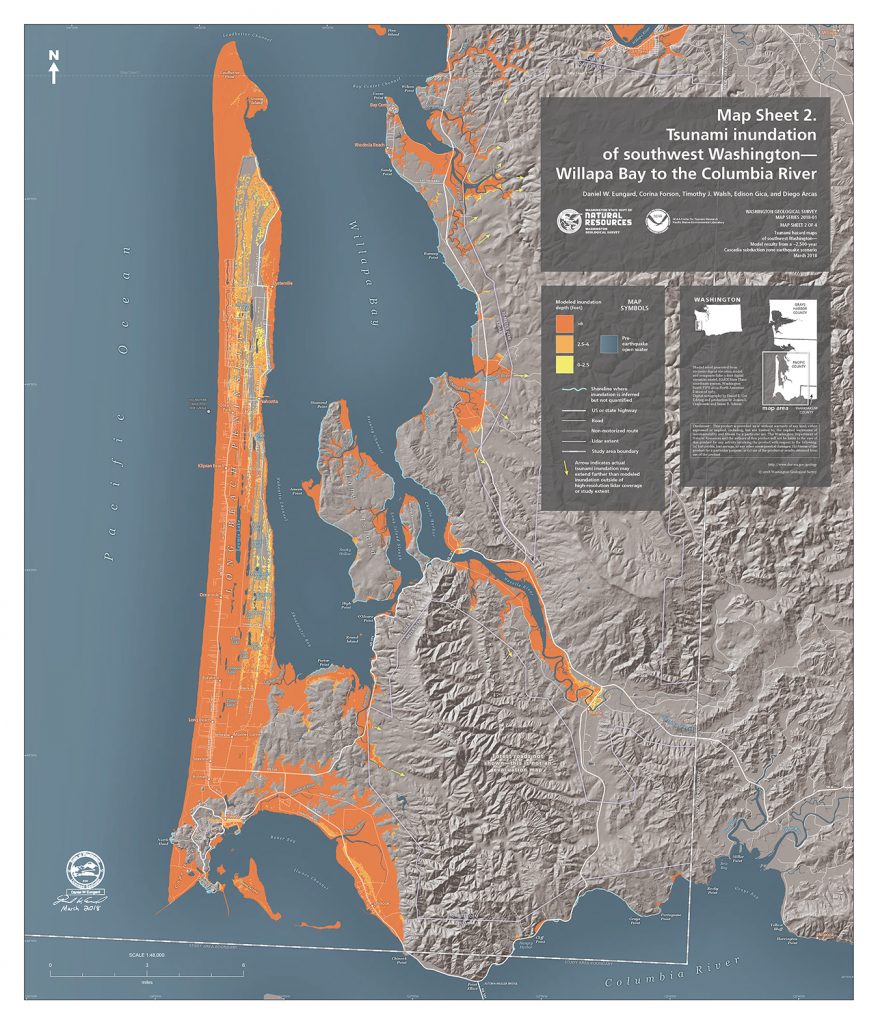

Last year, scientists published a model of how Grays Harbor and Pacific County would be hit with a massive wave following a 9.0 earthquake along the Cascadia Subduction Zone, the fault line that runs about 600-miles along the West Coast. And that is nasty.

In the study, researchers estimated how much time residents would have to prepare for a huge tsunami wave. Their guess? About 15 to 20 minutes.

Of course, that’d be following a mighty powerful earthquake as well.

“With a magnitude 9.0 event you’re expecting a severe amount of shaking,” Dan Eungard, one of the scientists who published the report, said.

“For the people on the outer coast all the way into Puget Sound, and essentially all of the western Washington area – and that extends as far down into northern California and lower British Columbia area as well – they would experience a strong degree of shaking. And when I say a strong degree of shaking, you would not be able to stand, you would be forced to the ground, just because you wouldn’t be able to hold your balance.“

The terrifying model

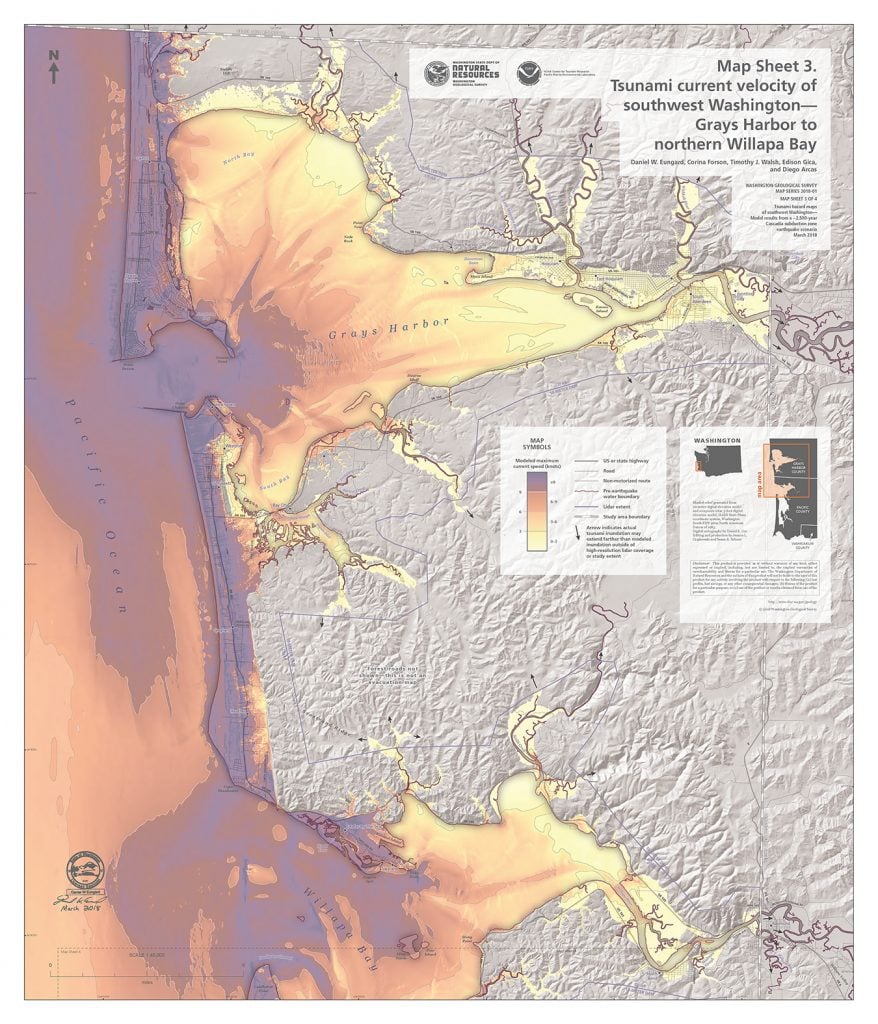

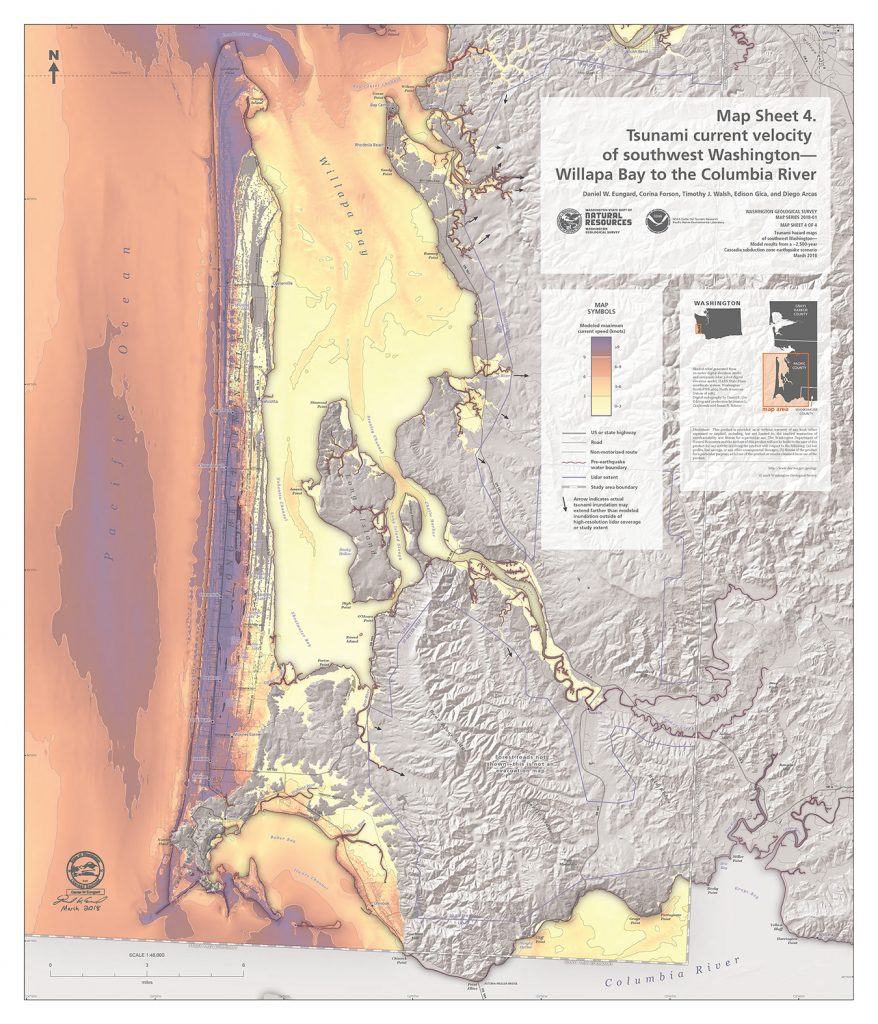

According to their model, a 9.0 earthquake struck the Zone, the first tsunami would arrive on land along the outer coasts mere minutes later, with the wave moving at speeds exceeding 40 miles per hour.

On the outer coasts that could mean inundation depth ranges from 20 to 60 feet; these rates decrease to generally less than 10 feet within Willapa Bay and Grays Harbor.

And there could be more than one wave, with potential follow-ups expected up to 12 hours after the initial quake.

This study can’t account for some specific details, like tidal effects or minor topographic changes that could modify the impact of tsunami waves. But they do believe this is an excellent tool for evacuation and recovery planning.

“The key takeaways of it are where do you live, where you work, where are the places you frequent most in your daily life? And that’s the kind of thing we want to draw people’s attention to … what we’re pushing for, more than anything, is personal preparedness,” Eungard said.

It’s another reason why Washington and other West Coast states have been pushing for record funding of the ShakeAlert system in the 2018 FY spending bill. ShakeAlert would cost about $38.2 million to build out along the West Coast, but could feasibly give people up to minutes of notice about an oncoming earthquake.

Eungard and his team believe that systems like that help, but it has to be a multi-step awareness for the coastal population in particular.

“It is a two-pronged hazard, when you think about it in the hazard preparedness: You’re preparing for the hazard, and you’re preparing for a tsunami. And many people divorce those into two separate categories. But essentially, you can’t have the tsunami without the earthquake as well,” Eungard said, noting that everyone should prepare for the earthquake in Western Washington as everyone will feel it.

“But then, depending on where you go and who you are, would depend on whether you also should be preparing for the tsunami as well. And definitely for the outer coast communities, they should be thinking of both of them as a simultaneous hazard scenario that they should be thinking of both at the same time.“

Are you prepared for the next Big One along the Cascadia? It could hit anytime now… And then it will be too late!

[Washington State Geology, uw.edu, Komonews]

Great post.