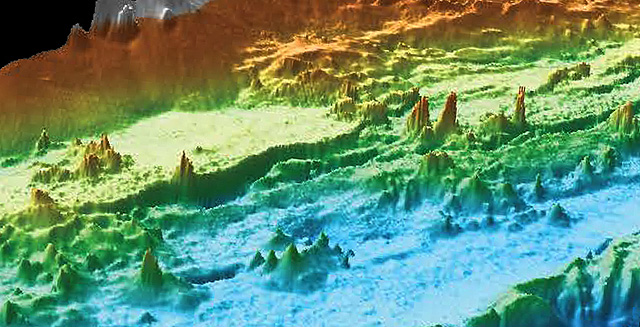

In the dark ocean depths off the coast of the Pacific Northwest, a magical fairyland of towering spires and hydrothermal chimneys sprout from the seafloor

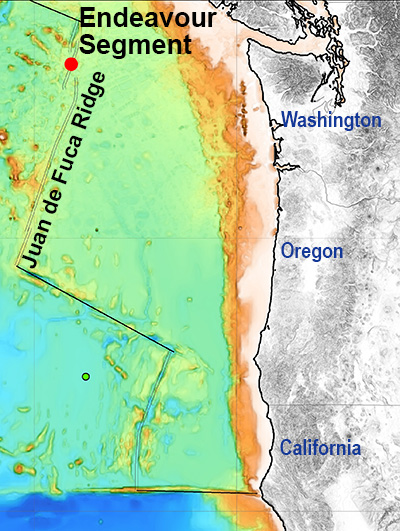

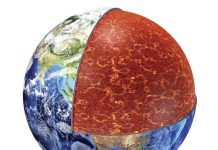

These towers situated in The Endeavour Segment of the Juan de Fuca Ridge, an active volcanic area far off the coast of the Pacific Northwest, belch superheated liquid warmed by magma deep inside Earth.

The field of hydrothermal chimneys stretches along the ocean bottom on the Juan de Fuca Ridge to the northwest of coastal Washington state, in an area known as the Endeavor Segment.

Research on the Endeavor vents began in the 1980s, and scientists had previously identified 47 chimneys in five major vent fields. But recent expeditions, using an autonomous underwater vehicle operated by the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI) revealed more than 500 chimneys in a zone about 9 miles (14 kilometers) long and 1 mile (2 km) wide.

Deep-sea chimneys

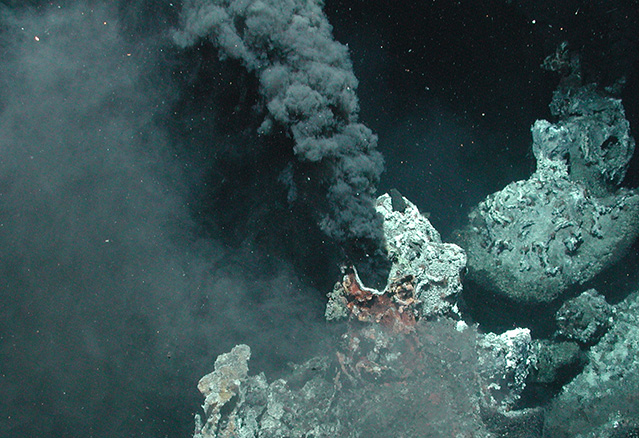

Deep-sea chimneys form around hydrothermal vents from a buildup of minerals that flow to the surface in heated liquid — as hot as 750 degrees Fahrenheit (400 degrees Celsius).

As hot liquid meets cold seawater, minerals precipitate and settle around the vent, collecting to form towers that can reach impressive heights.

Endeavor Segment

At the Endeavor Segment, “abundant and vigorous” hydrothermal activity has transformed the seafloor for approximately 2,300 years, and periods of intense seismic vibration shake things up even more, according to a new study on the MBARI expedition.

Chimneys that climb from Endeavor are among the tallest in any mid-ocean ridge; the biggest ever documented, a top-heavy tower known affectionately as “Godzilla,” extended 150 feet (45 meters) from the seafloor, but it crumbled in 1995.

Most of the five Endeavor vent fields have whimsical names:

- Main Endeavor Field: Main research destination

- High Rise

- Sasquatch

- Mothra

- Salty Dawg

Other vent sites are named “Quebec,” “Dune” and “Clam Bed,” according to the study.

High-res surveys

Prior expeditions struggled to identify seafloor structures in the depth and darkness of the vent fields. Sonar from surface vessels and explorations by diving robots couldn’t map the region at high enough resolution for researchers to count individual chimneys.

“It’s very hard to see down there because all the particulates in the water create a kind of haze,” said MBARI senior scientist, geologist and volcanologist David Clague.

And, “There was one well-studied chimney where the composition of the fluids seemed to vary from one research dive to the next. It wasn’t until we did our detailed mapping that people realized they had actually been sampling at two different chimneys.”

“They apparently would encounter one chimney or the other depending on what direction they approached the site.”

New study and results

This time, MBARI scientists took a closer look at the chimneys with the D. Allan B, a yellow torpedo-shaped AUV measuring about 17 feet (5 m) long and capable of mapping with multibeam sonar at a resolution of 4 feet (1 m), according to the new study.

The AUV performed four surveys in 2008 from the research vehicle Atlantis, and it conducted three surveys from the research vehicle Zephyr in 2011, enabling the scientists to generate a new map covering about 24 square miles (62 square km).

The study authors counted 572 chimneys that were taller than 10 feet (3 m) high — tall enough to be distinguished from other landscape features.

Most of the chimneys were under 26 feet (8 m) tall, though the tallest extended to heights of 90 feet (27 m) above the sea bottom.

Most of those chimneys were quiet. If mineral buildup blocks the chimney vent, superheated fluids divert to another crack and the chimney ceases to grow, though they can remain standing for centuries.

Only 47 of the Endeavor chimneys (those that were identified in previous maps) were active, the researchers reported.

By comparison, a similar hydrothermal field, Alarcón Rise in the Gulf of California, has only 109 chimneys mapped, but 31 of them are active.

Hydrothermal activity at Endeavor

Endeavor likely has more inert structures than Alarcón Rise because the latter lies in a more volcanically active region, and its older, inactive chimneys have been buried over time by lava flows, so you can’t see them, the researchers reported.

However, that may soon change. Geologic evidence from Endeavor and other vent fields suggests that hydrothermal activity is part of a cycle that reshapes the seafloor over many thousands of years.

Based on their work at Endeavour and other mid-ocean ridges, the researchers propose that these ridges may go through three phases of evolution:

- A magmatic phase, lasting up to tens of thousands of years, when large amounts of magma erupt and cover the seafloor with lava.

- A tectonic phase, lasting perhaps 5,000 years, when the magma supply slows, and the seafloor cools and contracts, while spreading continues deeper in the crust. During this phase, the axial valley sinks, and numerous cracks and faults form in the seafloor.

- A hydrothermal phase, lasting just a few thousand years, when resurgent magma below the surface heats fluids that percolate upwards through seafloor cracks, forming large numbers of vents.

So, Endeavor’s hydrothermal period may be winding down, to be replaced by a lava-spitting “magmatic phase” that can last tens of thousands of years.

When that happens, many of the newly mapped Endeavor structures may vanish — as did the older chimneys at Alarcón Rise.

And don’t forget, “Cascadia the Big One” is just around the corner (follow the link above or click on the picture below):

More geology news on Strange Sounds and Steve Quayle. [AGU, MBARI, LiveScience]

i like your articles keep up the good work