Scientists want to use the Moon as a giant cosmic ray detector to decipher one of the greatest mysteries in astrophysics: The ultra-high-energy (UHE) cosmic rays.

The signals of these particles (the most energetic in the Universe) are so short and fast that no radio telescope on Earth is currently capable of picking them up.

Scientists from the University of Southampton plan to turn the Moon into a giant particle detector to help understand the origin of ultra-high-energy (UHE) cosmic rays — the most energetic particles in the Universe.

The origin of UHE cosmic rays is one of the great mysteries in astrophysics. Nobody knows where these extremely rare cosmic rays come from or how they get their enormous energies. Physicists detect them on Earth at a rate of less than one particle per square kilometer per century.

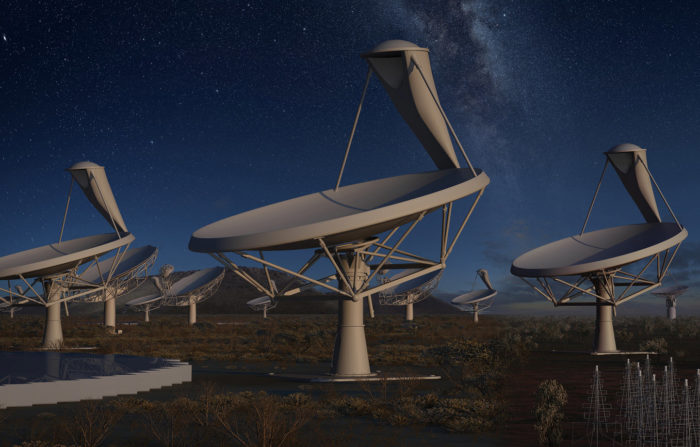

Justin Bray, a Research Fellow in Cosmic Magnetism at the University of Southampton, is lead author of a proposal to use the Square Kilometre Array (SKA) — set to become the largest and most sensitive radio telescope in the world — to detect vastly more UHE cosmic rays by using the Moon as a giant cosmic ray detector.

On Earth, physicists detect these high-energy particles when they hit the upper atmosphere triggering a cascade of secondary particles that generate a short and faint burst of radio waves only a few nanoseconds long.

Signals from the Moon

It is this signal that astronomers hope to pick up instead from the Moon, but these signals are so short and faint, so no radio telescope on Earth is currently capable of picking them up.

With its large collecting area and high sensitivity, the SKA will be able to detect these signals using the visible lunar surface (which measures millions of square kilometers) — giving the researchers access to more data about UHE cosmic rays than they have ever had before. Researchers hope to detect around 165 UHE cosmic rays a year from the Moon compared to the 15 a year currently observed.

With receivers across 33,0000 square kilometers in Australia and Africa, its dishes and antennas will also provide detailed information on the large-scale 3D structure of the Universe.

When operational in the early 2020’s, the SKA radio telescope dishes will produce 10 times the global Internet traffic data.