The flash of bright light surprised everyone who saw it. Hundreds of Portlanders reported spotting “a vast burst of smoke and spurting flame.” The explosion that followed was even more startling. The shock wave reverberated across the sky for miles, shattering windows and cracking walls. A Chelyabinsk event in the US… Just 80 years ago!

A recreational mountain climber might have had the best view.

“I was standing still for a moment, looking toward Portland,” recalled Thurston Skei, who was working his way up Mount Adams just before 8 a.m. on July 2, 1939. “I saw a trail of smoke coming down through the sky. There was a bright flash at the head of the smoke column as if a huge rocket had exploded.“

A few people called police to ask if Martians had attacked. This was nine months after Orson Welles’ War of the Worlds radio broadcast had confused and worried listeners. Many more residents thought there had been an earthquake. But the University of Washington’s seismograph had remained quiet.

The streak of light was, scientists soon announced, a “bolide, or exploding meteor.” It had appeared over Eugene at about 7:50 in the morning and was “big as the moon,” said one witness.

Experts later estimated the meteor was 50 miles high when it zipped past the college town.

University of Oregon astronomer J. Hugh Pruett immediately realized that the skittering flash in the sky was probably “one of the rare meteors large enough to penetrate the atmosphere and strike.” He hoped large fragments had survived and could be found. Harvard University scientists said it was “highly probable that something fell to earth” in Oregon.

In the years before the Space Age, such a visitor from beyond Earth’s bounds was a big deal.

“Learned astronomers and physicists have focused their powerful minds on an invisible trail blazed in the sky over Portland by the flight of a Sunday-morning meteor and profoundly concluded that something had happened there,” The Oregonian wrote. “That the meteor actually exploded from the conflict of its own terrific forces was declared by [University of California] Professor W.F. Meyer to be quite likely.”

By the time that article was published, U of O’s Pruett had already hastily organized a search team, which was spreading out in the Wind River area 40 miles northeast of Portland. The meteor hunters were told not to worry: they wouldn’t burn their hands if they found a fragment and picked it up. Sure, a meteor glows “white hot from air friction” when it crashes through Earth’s atmosphere, but its core retains “the temperature of 273 degrees below zero it had in the cold regions of outer space.”

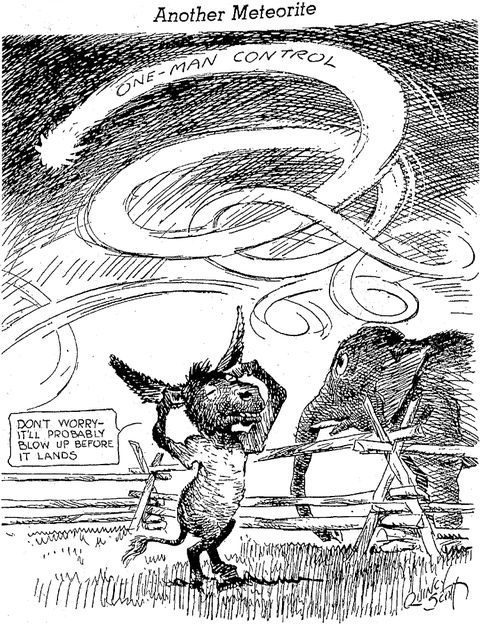

Interest stretched far beyond Oregon. In the days that followed the sighting, newspapers across the country waxed poetic about the meteor.

“Consider a hunk of rock as big as an elephant, more or less, hurtling through the frigid silence of empty space,” one reporter wrote. “It may have been going, unresisted, for a million years; its speed anything up to 50 miles a second, its temperature 460 degrees below zero Fahrenheit. Suddenly the fragment crashes into the thin outer layer of Earth’s atmosphere. The friction is so great that the surface of the rock melts and boils and flows away in flaming gas.”

And the reporting captured more than the beauty and majesty of the happening.

“Persons who dared to speculate on what a fair-sized meteor could do to a city like Portland were devoutly thankful it missed,” The Oregonian wrote.

The New York Times embraced the same theme, stating that an especially large meteor “could theoretically destroy much of a great city.“

This wasn’t just pandering to readers’ fears: it was an acknowledgement of a known possibility. There had been an epically destructive meteor strike in Siberia in 1908, and another large space rock had reportedly crashed in Brazil 22 years later. In 2013, a 65-foot-wide meteor would explode over the Russian city of Chelyabinsk, blowing out windows in thousands of buildings and causing minor injuries to hundreds of residents.

“These events are not rare,” NASA administrator Jim Bridenstine said Monday. “They happen.”

In the wake of the earth-shaking event in 1939, Oregon became meteor-mad — but hunters ultimately found the search for their space rock frustrating. One Portland woman sparked a flurry of excitement when she brought forth “a hard, fused mass” she found in her yard a few minutes after hearing the early-morning explosion. Analysis of the object, however, showed it to be burned coal, probably jarred from the chimney by the air concussion.”

Which was probably just as well. No meteor fragment could possibly live up to what so many people in the area believed they had witnessed.

“The noise I heard was a bedlam and indescribable confusion as of the shrieking and scraping of many auto breaks,” Prescott resident Mrs. D.L. Stevens wrote in a letter. “Shrieks and wails as if of human voices, beside a great many other sounds not to be described, as if any and every sound known or imagined had been included, except living voices.“

Yes, meteorites make bizarre noises when they burn in our atmosphere.