A new analysis of two ancient Egyptian mummies has uncovered the earliest known examples of “figural” tattoos on human beings – that is, tattoos that are meant to represent a real things, rather than abstract symbols. What’s more, at around 5,000 years old, it’s the earliest evidence of tattoos on a woman.

The two mummies, one female and one male, have been on display at the British Museum for decades. They were discovered about 100 years ago in Gebelein, which is about 25 miles (40 km) south of Luxor, Egypt. The bodies—dubbed “Gebelein Woman” and “Gebelin Man A”—were found buried in a shallow grave, and without any special treatments; the desert’s dryness, salinity, and heat prevented the bodies from decaying, which is why they were found in such remarkably good condition. The mummies were dated to between 3351 and 3017 BC—the Predynastic period of ancient Egypt, a time before the first pharaoh unified the fledgling nation.

Under normal lighting, faint markings were visible on both mummies, but scientists didn’t think much of them, assuming they were unimportant. Daniel Antoine, curator of physical anthropology at the British Museum, along with his colleagues from Oxford University and the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, decided to take a closer look at these markings using the latest scientific techniques, including CT scanning, radiocarbon dating, and infrared imaging. The resulting analysis, now published in the Journal of Archaeological Science, changes what we know of these mummies and the era in which they lived.

“Only now are we gaining new insights into the lives of these remarkably preserved individuals,” said Antoine in a statement. “Incredibly, at over 5,000 years of age, they push back the evidence for tattooing in Africa by a millennium.”

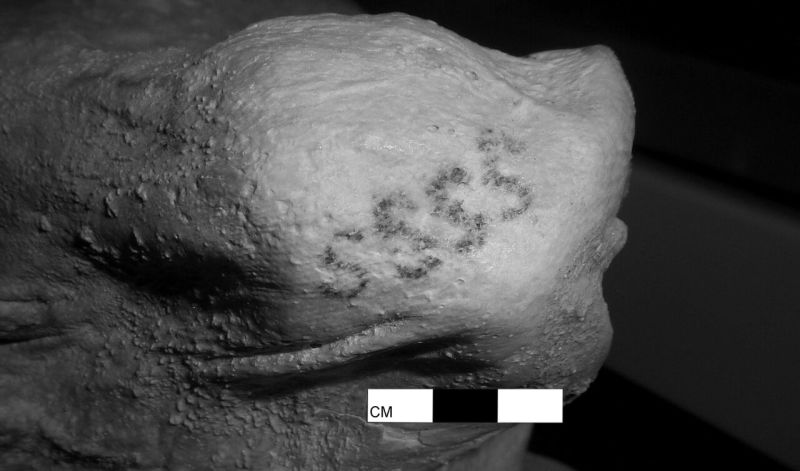

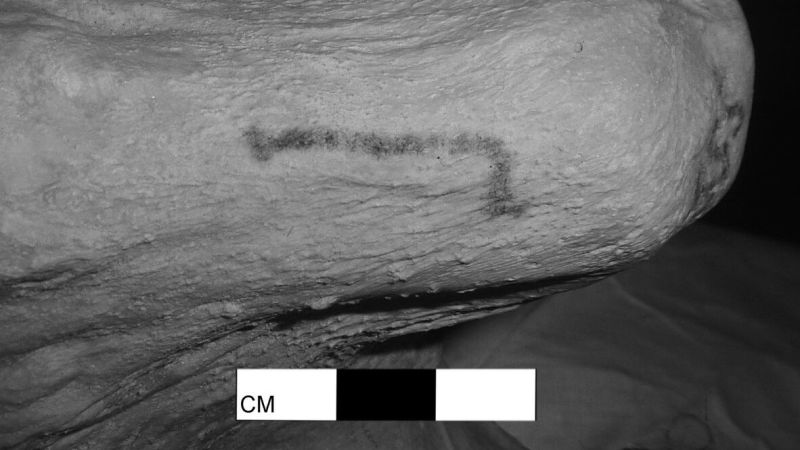

The markings on these mummies are now the oldest evidence of figural tattoos on humans. These weren’t just etchings made on the skin—they were actual representations, or drawings, of physical objects. Gebelin Man A had tattoos of what appears to be a wild bull and a sheep, while Gebelein Woman had staff-like and S-shaped motifs on her upper arm and shoulder. The tattoos may have indicated status or bravery, or they may have held spiritual importance, like an indication of special knowledge or protective powers. The discovery also shows that tattooing was practiced by both sexes at the time. The carbon-based pigment, perhaps soot, was applied to the dermis layer of the skin.

Using infrared photography, the researchers identified a series of four small ‘S’ shaped motifs running vertically across Gebelein Woman’s right shoulder. This motif was quite common during this era, appearing on Predynastic pottery and always in multiples. The linear motif on her right arm bears a striking resemblance to objects seen in painted ceramics of the same period, in which individuals hold onto objects while engaging in ceremonial activities. The crooked stave could be a symbol of power and status, a throwing stick, or a baton used in ritual dances. They’re the earliest known examples of tattoos on a female in the paleoarchaeological record.

Previous CT scans showed that the male was between the age of 18 and 21 when he died, and that he was killed by a stab wound to the back. The researchers were able to discern his markings as being tattoos of slightly overlapping horned animals—likely a wild bull with its long tail and elaborate horns, and a Barbary sheep with its curving horns and slumped shoulder. Both animals were common in Egypt at the time.

PUBLIC SECURITY SECTION 9 AGENT ISHIKAWA SAYS: I have to tattoo of a Japanese battle tank on my right calf. On my upper left arm is a tattoo of a communications complex! Those are the trades that I work in.

[…] article source […]