California’s Hayward Fault is considered one of the most dangerous seismological zones in the United States.

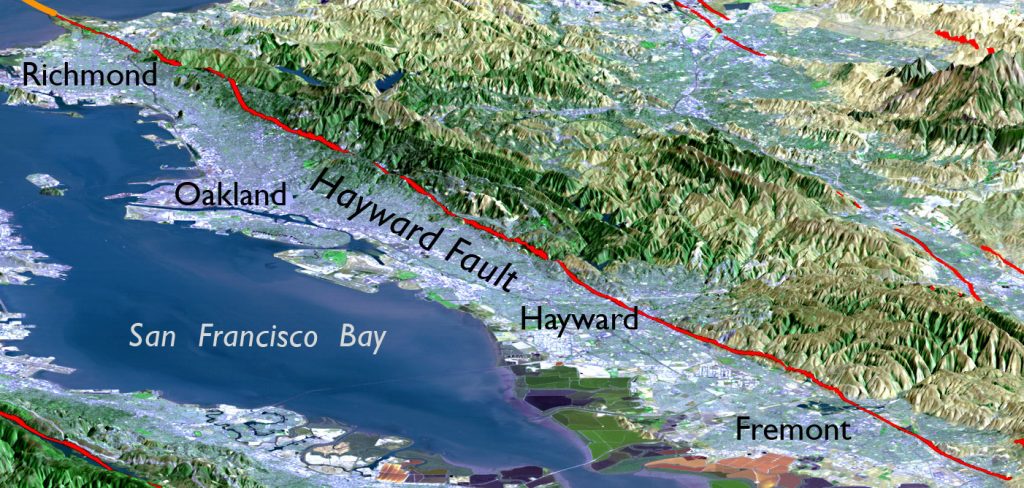

It runs through the densely populated hills of the East Bay, sketching a diagonal line between San Jose and Richmond and can be thought of as a branch of the main trunk of the San Andreas.

Technically speaking, the Hayward is a right-lateral strike-slip fault. This means that it shows its everyday action in the form of aseismic creep, the slow, steady sliding of land along the fault’s margin.

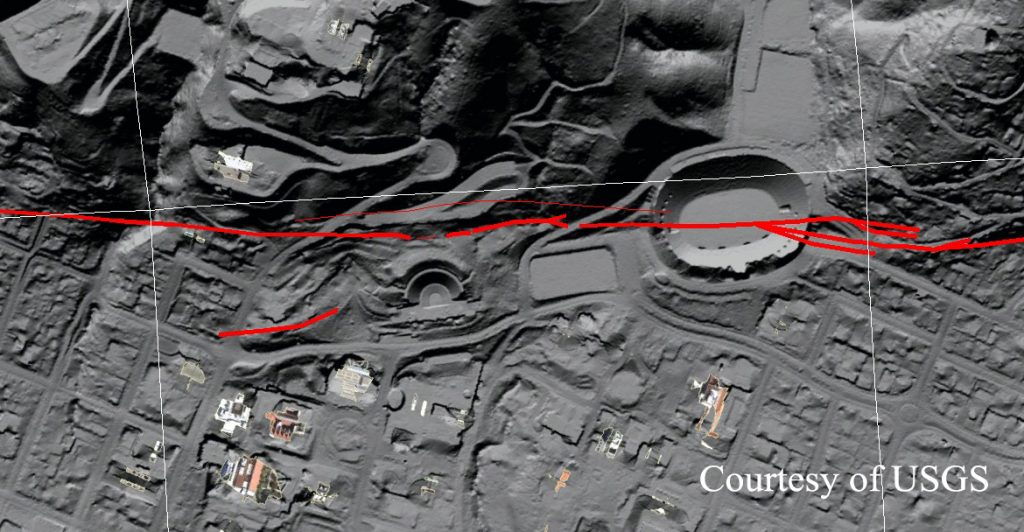

The symptoms of this tectonic origami are visible across the region in cracked asphalt, off-kilter curbstones, and leaning walls.

Every day, people drive on roads and hike on trails that crisscross the Hayward. Children attend a school and play soccer on fields that straddle it.

All of which is to say that the Hayward cuts an uncanny transect through the lives of hundreds of thousands of Bay Area residents.

According to the U.S. Geological Survey, the average rate of creep on the Hayward is 4.6 millimetres per year or about the length of a standard black garden ant, or a quarter of a jelly bean.

Not a big deal you think! But the engine of this movement is far to the south, in the Gulf of California, where the seabed along the margin of the Pacific and North American Plates is spreading apart, putting pressure, in turn, on the San Andreas Fault.

The sliding poses a threat to the built environment, of course, but it also has a beneficial function. In one sense, creep is our enemy, since it can damage buildings and infrastructure. In another sense, creep is our friend, because it helps relieve the strain on fault lines.

The Big Problem

What makes the Hayward so concerning is that it is not creeping quickly enough.

In theory, it should be slipping about ten millimetres a year, roughly twice its observed rate.

Over time, the deficit mounts until the rock formations along the fault can no longer tolerate it.

That distance has to be accommodated eventually by sudden land movement, which is an earthquake.

Studies of pond sediments along the fault suggest that these large, strain-relieving tremors have happened regularly in the past.

It has been calculated that they occur every hundred and forty or hundred and fifty years. The last one took place on October 21, 1868 – a hundred and forty-eight years ago – and caused significant damage.

Dozens of buildings, including an eighteenth-century Spanish mission in Fremont, were destroyed, and a twenty-mile-long crack opened in the earth between Fremont and Oakland.

Miraculously, only thirty people were killed, largely because the population of the Bay Area was about four per cent of its present-day size.

Until 1906, when a magnitude-7.8 quake devastated San Francisco, the Hayward event was known across the region as “the big one.”

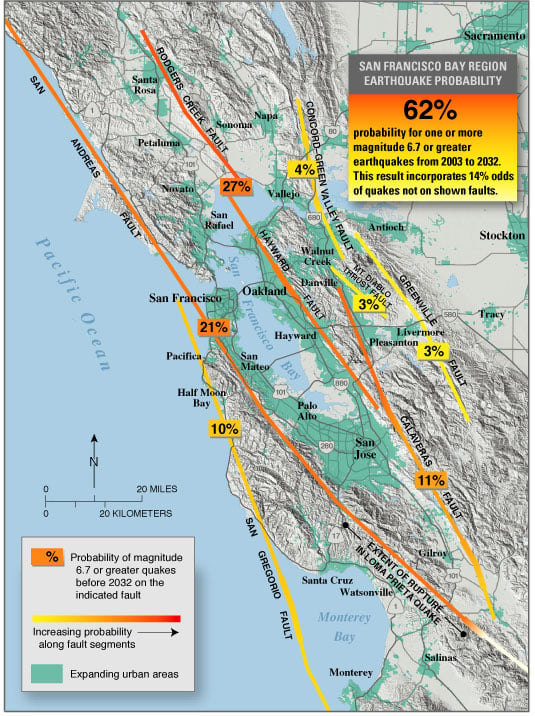

Seismologists aren’t sure whether the Hayward’s current built-up tectonic stress will be relieved in one large tremor or a series of smaller, less damaging ones.

But what seems certain is that a repeat of the 1868 event would be catastrophic, resulting in heavy damage to thousands of structures and likely causing hundreds of deaths.

A Hayward-based company called Risk Management Solutions has estimated that a magnitude-7.0 quake would result in between ninety-five billion and a hundred and ninety billion dollars in damage to commercial and residential property.

An earlier study by the Association of Bay Area Governments laid out a “nightmare” scenario, predicting the destruction of a hundred and fifty-five thousand housing units and the displacement of three hundred and sixty thousand people.

The average amount of slip in the magnitude-7.0 quake scenarios is four feet – two hundred and sixty-five years’ worth of aseismic creep triggered in an instant.

Is the Hayward Fault the Most Dangerous Fault in the U.S.?

First, a map of the major earthquake fault lines in the USA.

Of course you have the San Andreas and its many subsidiaries in and around Los Angeles.

You also have the Cascadia subduction zone, which, when it eventually ruptures, could produce a tsunami that would inundate swaths of the Pacific Northwest.

But the threat of the East Bay faults are more immediate. Since 1906, enough strain has accumulated for a couple of magnitude-7.0 earthquakes.

Whichever fault you pick, it’s just time.

[via The New Yorker]

One of the most dangerous was an earthquake that changed the course of the Mississippi River in the early 1800s. If it would occur today…it would be extremely deadly.

Yes you are talking about the New Madrid fault system. If this one erupts it will also end deadly. But the population density is lower over there than living over the Hayward fault.

[…] The Hayward Fault in California is the most dangerous earthquake fault in the USA and the single mos… […]

[…] Klik:>https://strangesounds.org/2018/03/hayward-fault-california-most-dangerous-earthquake-fault-usa-map-vi… […]