Floods, hurricanes, storm surges.

Does Louisiana need to add tsunami to its list of threats?

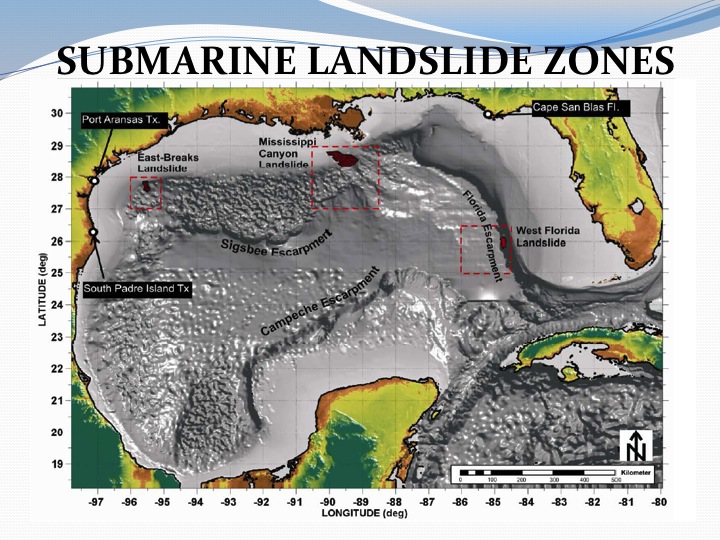

A 15-foot wall of water could roll across Grand Isle if a landslide occurred in the Mississippi Canyon, a trench in the Gulf of Mexico floor about 30 miles off the mouth of the Mississippi River.

And unlike a hurricane, residents would have just an hour’s notice – not days.

Such landslides have happened about once every 1,000 years in that area, and that time frame is almost up.

Low Probability event

Although being a low probability event — one in a thousand — it still is a credible event, and would be of a high impact.

The National Weather Service (NWS) has found evidence of previous slides in the canyon, which could cause significant tsunamis.

The material falling into the canyon would displace the water that is already there, and that would cause the wave.

The following video shows a physics-based computer simulation of a tsunami generated by a submarine landslide in the Gulf of Mexico about 7000 years ago. The 500 cubic km landslide occurred in Mississippi Canyon and generated tsunamis from 2 to 20 meters which reached all shores of the Gulf.

It wouldn’t be very noticeable in the open Gulf, but as the wave reached the shallower water near the shore, it would rise up.

The hypothetical landslide used in National Weather Service computer model was 13 miles wide, 40 miles long and dumped enough rocks and sediment into the canyon to fill 38 Superdomes.

The resulting tsunami waves would reached about 14 to 15 feet at Grand Isle, 10.5 feet in St. Mary Parish, and about 4 feet in Cameron Parish.

So what would cause such a tsunami?

The likely trigger of a future slide would be:

- strong seismic activity (>M7.0), which has been rare in this area

- the eruption of large gas bubbles through the sediment layers at the base of the area

- a giant underwater landslide on the edge of the canyon.

How do landslides cause tsunamis?

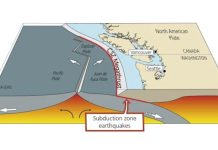

Tsunamis are large, potentially deadly and destructive sea waves, most of which are formed as a result of submarine earthquakes. They can also result from the eruption or collapse of island or coastal volcanoes and from giant landslides on marine margins. These landslides, in turn, are often triggered by earthquakes. Tsunamis can be generated on impact as a rapidly moving landslide mass enters the water or as water displaces behind and ahead of a rapidly moving underwater landslide.

Research in the Canary Islands (off the northwestern coast of Africa) concludes that there have been at least five massive volcano landslides that occurred in the past, and that similar large events might occur in the future. Giant landslides in the Canary Islands could potentially generate large tsunami waves at both close and very great distances, and could potentially devastate large areas of coastal land as far away as the eastern seaboard of North America.

Rock falls and rock avalanches in coastal inlets, such as those that have occurred in the past at Tidal Inlet in Alaska’s Glacier Bay National Park, have the potential to cause regional tsunamis that pose a hazard to coastal ecosystems and human settlements. On July 9, 1958, a magnitude 7.9 earthquake on the Fairweather Fault triggered a rock avalanche at the head of Lituya Bay, Alaska. The landslide generated a wave that ran up 524 meters (1,719 feet) on the opposite shore and sent a 30-meter-high wave through Lituya Bay, sinking two fishing boats and killing two people.

What is the difference between a tsunami and a tidal wave?

Although both are sea waves, a tsunami and a tidal wave are two different and unrelated phenomena. A tidal wave is a shallow water wave caused by the gravitational interactions between the Sun, Moon, and Earth (“tidal wave” was used in earlier times to describe what we now call a tsunami).

A tsunami is an ocean wave triggered by large earthquakes that occur near or under the ocean, volcanic eruptions, submarine landslides, or by onshore landslides in which large volumes of debris fall into the water.

Gulf Tsunamis LCH (1) by thelensnola on Scribd

If you thought sinking land and rising seas were the only things they had to worry about in south Louisiana, think again. Tsunamis have now joined the list.

More geology news on Strange Sounds and Steve Quayle. [The Lens]

[…] STRANGE SOUNDS REPORT HERE […]