The hunt for new physics is back on. The world’s most powerful machine for smashing high-energy particles together, the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), has fired up after a shutdown of more than three years. Beams of protons are once again whizzing around its 27-kilometre loop at CERN, Europe’s particle-physics laboratory near Geneva. As of today, July 5th, physicists will be able to switch on their experiments and watch bunches of particles collide.

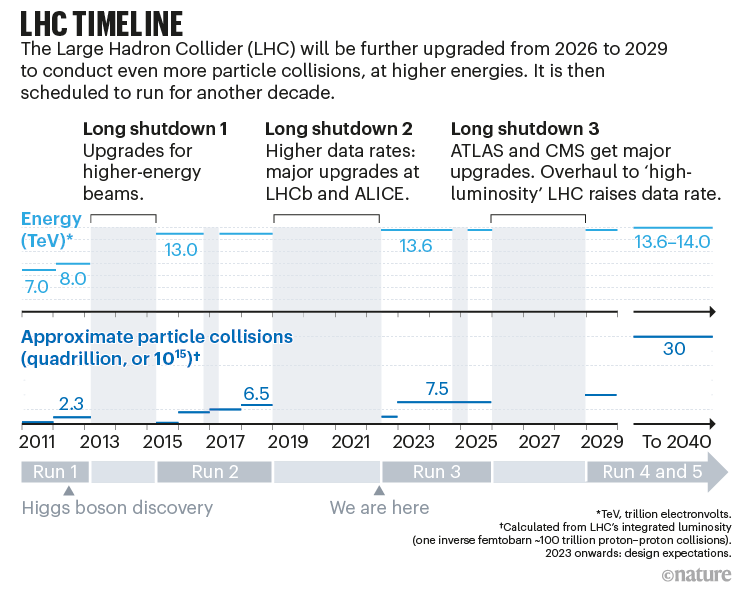

In its first two stints, in 2009–13 and 2015–18, the LHC explored the known physics world. All of that work — including the triumphant 2012 discovery of the Higgs boson — reaffirmed physicists’ current best description of the particles and forces that make up the Universe: the standard model. But scientists sifting through the detritus of quadrillions of high-energy collisions have yet to find proof of any surprising new particles or anything else completely unknown.

This time could be different. The LHC has so far cost US$9.2 billion to build, including the latest upgrades: version three comes with more data, better detectors and innovative ways to search for new physics. What’s more, scientists start with a tantalizing shopping list of anomalous results — many more than at the start of the last run — that hint at where to look for particles outside the standard model.

“We’re really starting with adrenaline up,” says Isabel Pedraza, a particle physicist at the Meritorious Autonomous University of Puebla (BUAP) in Mexico. “I’m sure we will see something in run 3.”

Higher energy and more data

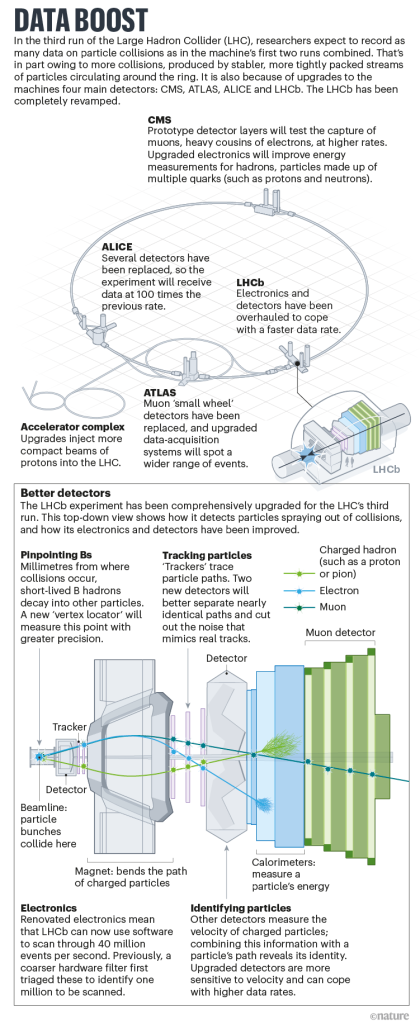

After renovations to its particle accelerators, the third version of the LHC will collide protons at 13.6 trillion electron volts (TeV) — slightly higher than in run 2, which reached 13 TeV.

The more-energetic smashes should increase the chances that collisions will create particles in high-energy regions where some theories suggest new physics could lie, says Rende Steerenberg, who leads beam operations at CERN.

The machine’s beams will also deliver more-compact bunches of particles, increasing the probability of collisions. This will allow the LHC to maintain its peak rate of collisions for longer, ultimately allowing experiments to record as many data as in the first two runs combined.

To deal with the flood, the machine’s detectors — layers of sensors that capture particles that spray from collisions and measure their energy, momentum and other properties — have been upgraded to make them more efficient and precise.

A major challenge for LHC researchers has always been that so little of the collision data can be stored. The machine collides bunches 40 million times per second, and each proton–proton collision, or ‘event’, can spew out hundreds of particles. ‘Trigger’ systems must weed out the most interesting of these events and throw the bulk of the data away.

Prepare now! You will never go without electricity with this portable power station…

For example, at CMS — one of the LHC’s four main experiments — a trigger built into the hardware makes a rough cut of around 100,000 events per second on the basis of assessments of properties such as the particles’ energies, before software picks out around 1,000 to reconstruct in full for analysis.

With more data, the trigger systems must triage even more events. One improvement comes from a trial of chips originally designed for video games, called GPUs (graphics processing units). These can reconstruct particle histories more quickly than conventional processors can, so the software will be able to scan faster and across more criteria each second. That will allow it to potentially spot strange collisions that might previously have been missed.

In particular, the LHCb experiment has revamped its detector electronics so that it will use only software to scan events for interesting physics. Improvements across the experiment mean that it should collect four times more data in run 3 than it did in run 2. It is “almost like a brand new detector”, says Yasmine Amhis, a physicist at the Laboratory of the Irène-Joliot Curie Physics of the Two Infinities Lab in Orsay, France, and member of the LHCb collaboration.

Spotting anomalies

Run 3 will also give physicists more precision in their measurements of known particles, such as the Higgs boson, says Ludovico Pontecorvo, a physicist with the ATLAS experiment. This alone could produce results that conflict with known physics — for instance, when measuring it more precisely shrinks the error bars enough to put it outside the standard model’s predictions.

But physicists also want to know whether a host of odd recent results are genuine anomalies, which might help to fill some gaps in understanding about the Universe. The standard model is incomplete: it cannot account for phenomena such as dark matter, for instance. And findings that jar with the model — but are not firm enough to claim as a definite discrepancy — have popped up many times in the past two years.

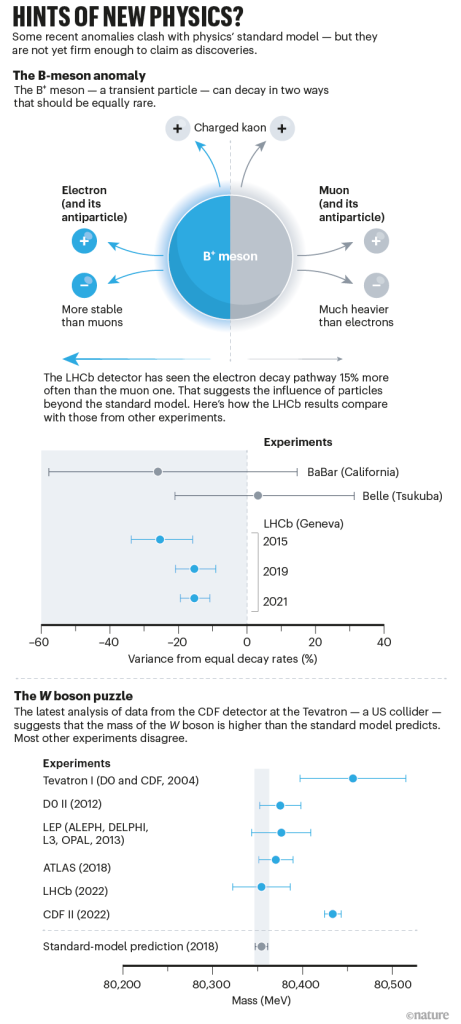

The most recent is from the Tevatron collider at the Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory (Fermilab) in Batavia, Illinois, which shut down in 2011. Researchers have spent the past decade poring through data from the Tevatron’s CDF experiment. In April, they reported1 that the mass of the W boson, a fundamental particle that carries the weak nuclear force involved in radioactive decay, is significantly higher than the standard model predicts.

That doesn’t chime with LHC data: measurements at ATLAS and LHCb disagree with the CDF data, although they are less precise. Physicists at CMS are now working on their own measurement, using data from the machine’s second run. Data from run 3 could provide a definitive answer, although not immediately, because the mass of the W boson is notoriously difficult to measure.

B-meson confusion

The LHC’s data have hinted at other anomalies. In particular, evidence has been building for almost a decade of odd behaviour in particles called B mesons. These transient particles, which quickly decay into others, are so named because they contain pairs of fundamental particles that include a ‘bottom’ or ‘beauty’ quark. LHCb analyses suggest that B-meson decays tend to produce electrons more often than they produce their heavier cousins, muons2.

The standard model predicts that nature should not prefer one over the other, says Tara Shears, a particle physicist at the University of Liverpool, UK, and a member of the LHCb collaboration. “Muons are being produced about 15% less often than electrons, and it’s utterly bizarre,” she says.

The result differs from the predictions of the standard model with a significance of around 3 sigma, or 3 standard deviations from what’s expected — which translates to a 3 in 1,000 chance that random noise could have produced the apparent bias. Only more data can confirm whether the effect is real or a statistical fluke.

Experimentalists might have misunderstood something in their data or machine, but now that many of the relevant LHCb detectors have been replaced, the next phase of data-gathering should provide a cross-check, Shears says. “We will be crushed if [the anomaly] goes away. But that’s life as a scientist, that can happen.”

The anomaly is backed up by similar subtle discrepancies that LHCb has seen in other decays involving bottom quarks; experiments at colliders in Japan and the United States have also seen hints of this odd result. This kind of work is LHCb’s métier: its detectors were designed to study in detail the decays of particles that contain heavy quarks, allowing the experiment to gather indirect hints of phenomena that might influence these particles’ behaviour.

CMS and ATLAS are more general-purpose experiments, but experimenters there are now checking to see whether they can spot more of the events that are sensitive to the anomalies, says Florencia Canelli, an experimental particle physicist at the University of Zurich in Switzerland and member of the CMS collaboration.

Hunt for the leptoquark

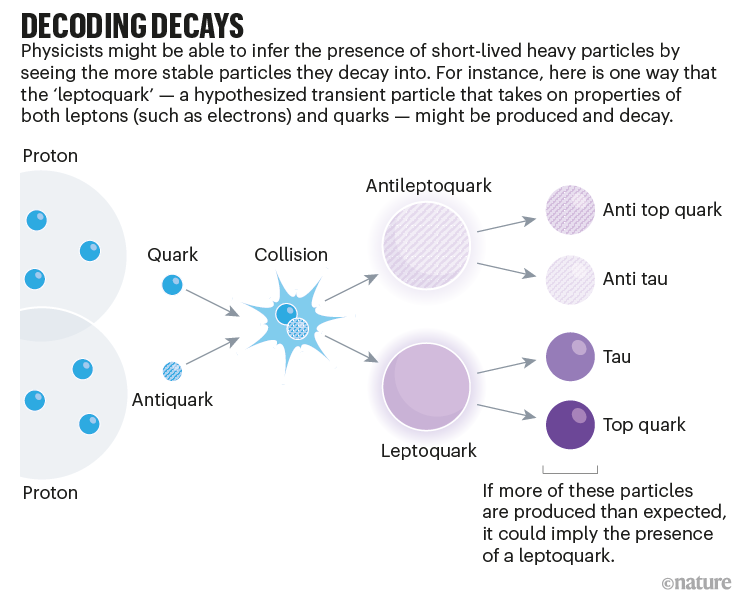

CMS and ATLAS will also do what LHCb cannot: comb collision data to look directly for the exotic particles that theorists suggest could be causing the still-unconfirmed anomalies. One such hypothetical particle has been dubbed the leptoquark, because it would, at high energies, take on properties of two otherwise distinct families of particles — leptons, such as electrons and muons, and quarks (see ‘Decoding decays’).

This hybrid particle comes from theories that seek to unite the electromagnetic, weak and strong fundamental forces as aspects of the same force, and could explain the LHCb results. The leptoquark — or a complex version of it — also fits with another tantalizing anomaly; a measurement last year3, from the Muon g − 2 experiment at Fermilab, that muons are more magnetic than expected.

At the Moriond particle-physics conference in La Thuile, Italy, in March, CMS researchers presented results of a search that found intriguing hints of a beyond-standard-model lepton. This particle would interact with leptoquarks and is predicted by some leptoquark theories. Physicists saw a slight excess of the particles that the proposed lepton could decay into, bottom quarks and taus (heavier cousins of the muon), but the finding’s significance is only 2.8 sigma.

“Those are very exciting results, as LHCb is also seeing something similar,” says Pedraza. CMS physicists presented hints of other new phenomena at the conference: two possible particles that might decay into two taus, and a potential high-energy particle that, through a theorized but unproven decay route, would turn into distinctive particle cascades termed jets.

Another intriguing result comes from ATLAS, where Ismet Siral at the University of Oregon in Eugene and his colleagues looked for hypothetical heavy, long-lived charged particles.

In trillions of collisions from 3 years of data they found 7 candidates at around 1.4 TeV, around 8 times the energy of the heaviest known particle4. Those results are 3.3 sigma, and the identity of the candidate particles remains a mystery. “We don’t know if this is real, we need more data. That’s where run 3 comes in,” says Siral.

Another LHC experiment, ALICE, will explore its own surprising finding: that the extreme conditions created in collisions between lead ions (which the LHC smashes together when not working with protons) might crop up elsewhere. ALICE is designed to study quark–gluon plasma, a hot, dense soup of fundamental particles created in collisions of heavy ions that is thought to have existed just after the Big Bang.

Analyses of the first two runs found that particles in proton–proton and proton–lead ion collisions show some traits of this state of matter, such as paths that are correlated rather than random. “It’s an extremely interesting, unexpected phenomenon,” says Barbara Erazmus, deputy spokesperson for ALICE at CERN.

Like LHCb, ALICE has had a major upgrade, including updated electronics to provide it with a faster software-only trigger system. The experiment, which will probe the temperature of the plasma as well as precisely measuring particles that contain charm and beauty quarks, will be able to collect 100 times more events this time than in its previous two runs, thanks to improvements across its detectors.

Machine learning aids the search

Run 3 will see also entirely new experiments. FASER, half a kilometre from ATLAS, will hunt for light and weakly interacting particles including neutrinos and new phenomena that could explain dark matter. (These particles can’t be spotted by ATLAS, because they would fly out of collisions on a trajectory that hugs close to the LHC’s beamline and evades the detectors). Meanwhile, the ATLAS and CMS experiments now have improved detectors but will not receive major hardware upgrades until the next long shutdown, in 2026.

At this point, the LHC will be overhauled to create more focused ‘high-luminosity’ beams, which will start up in 2029 (see ‘LHC timeline’). This will allow scientists in the following runs to collect 10 times more collision data than in runs 1 to 3 combined. For now, CMS and ATLAS have got prototype technology to help them prepare.

As well as collecting more events, physicists such as Siral are keen to change the way in which LHC experiments hunt for particles. So far, much of the LHC’s research has involved testing specific predictions (such as searching for the Higgs where physicists expected to see it) or hunting for particular hypotheses of new physics.

Drink clean water at home… Get this filter now…

Scientists thought this would be a fruitful strategy, because they had a good steer on where to look. Many expected to find new heavy particles, such as those predicted by a group of theories known as supersymmetry, soon after the LHC started. That they have seen none rules out all but the most convoluted versions of supersymmetry. Today, few theoretical extensions of the standard model seem any more likely to be true than others.

Experimentalists are now shifting to search strategies that are less constrained by expectations. Both ATLAS and CMS are going to search for long-lived particles that could linger across two collisions, for instance. New search strategies often mean writing analysis software that rejects the usual assumptions, says Siral.

Machine learning is likely to help, too. Many LHC experiments already use this technique to distinguish particular sought-for collisions from the background noise. This is ‘supervised’ learning: the algorithm is given a pattern to hunt for. But researchers are increasingly using ‘unsupervised’ machine-learning algorithms that can scan widely for anomalies, without expectations.

For example, a neural network can compare events against a learned simulation of the standard model. If the simulation can’t recreate the event, that’s an anomaly. Although this kind of approach is not yet used systematically, “I do think this is the direction people will go in,” says Sascha Caron of Radboud University Nijmegen in the Netherlands, who works on applying these techniques to ATLAS data.

In making searches less biased, the triggers that decide which events are interesting to look at are crucial, so it helps that the new GPUs will be able to scour candidate events with wider criteria. CMS will also use an approach called ‘scouting’: analysing rough reconstructions of all the 100,000 or so events initially selected but not saved in full detail. “It’s the equivalent of 10 years more of running your detector, but in one year,” says Andrea Massironi, a physicist with the CMS experiment.

The triggers themselves could also soon rely on machine learning to make their choices. Katya Govorkova, a particle physicist at CERN, and her colleagues have come up with a high-speed proof-of-principle algorithm that uses machine learning to select which of the collider’s 40 million events per second to save, according to their fit with the standard model5.

In run 3, researchers plan to train and test the algorithm on CMS collisions, alongside the experiment’s conventional trigger. A challenge will be knowing how to analyse events that the algorithm labels as anomalous, because it cannot yet point to exactly why an event is anomalous, says Govorkova.

Physicists must keep an open mind about where they might find the thread that will lead them to a theory beyond the standard model, says Amhis. Although the current crop of anomalies is exciting, even previous oddities seen by multiple experiments turned out to be statistical flukes that faded away when more data were gathered. “It’s important that we continue to push all of the physics programme,” she says. “It’s a matter of not putting all your eggs in one basket.” [Nature]

StrangeSounds.org has been banned from ad networks and is now entirely reader-supported CLICK HERE TO SUPPORT MY WORK… I will send you a small gemstone if you give more than 25$… Thanks in advance!

Here some things to add to your disaster & preparedness kit:

- Protect your home and car with the best EMP, solar flares and lightning shield available…

- Drink clean water at home… Get this filter now…

- Health Ranger Store: Buy Clean Food and Products to heal the world…

- Prepare your retirement by investing in GOLD, SILVER and other PRECIOUS METALS…

- You will ALWAYS have electricity with this portable SOLAR power station…

- Qfiles is another great site for alternative news and information…

This is the key to the bottomless pit. Prepare.

Georgia Guidestones Partially Blown Up

In Revolutionary Act Against The NWO – Video

https://www.wyff4.com/article/georgia-guidestones-possible-explosion/40525569

We have no responsibility for news no endorse it nor promote it.

our job is to show both sides of coin to promote truth for all.

This was done by the elites. Masonic ritual. And only the side with Hebrew and Arabic was blown up, prior to tearing down the rest

Yes, because they worship darkness/dark matter. And not only that, but CERN isn’t using green energy either.

The laboratory has had to innovate to keep up with it’s electrical demands. CERN uses 1.3 terawatt hours of electricity annually. That’s enough power to fuel 300,000 homes for a year in the United Kingdom. Run 3 will consume even more power.

https://home.cern/science/engineering/powering-cern#:~:text=CERN%20uses%201.3%20terawatt%20hours,the%20experimental%20requirements%20are%20adjusted.

Energy prices will go through the roof, or dare I say, through a parallel universe, or black hole! Perhaps what Stephen Hawking had said about the Biggs boson/God particle will finally come true. Most likely Revelation, about a new heaven and new earth, because the former passes away.

How CERN Is Using Linux and Open Source

By

Swapnil Bhartiya –

May 24, 2018

3301

CERN really needs no introduction. Among other things, the European Organization for Nuclear Research created the World Wide Web and the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), the world’s largest particle accelerator, which was used in discovery of the Higgs boson. Tim Bell, who is responsible for the organization’s IT Operating Systems and Infrastructure group, says the goal of his team is “to provide the compute facility for 13,000 physicists around the world to analyze those collisions, understand what the universe is made of and how it works.”

CERN is conducting hardcore science, especially with the LHC, which generates massive amounts of data when it’s operational. “CERN currently stores about 200 petabytes of data, with over 10 petabytes of data coming in each month when the accelerator is running. This certainly produces extreme challenges for the computing infrastructure, regarding storing this large amount of data, as well as the having the capability to process it in a reasonable timeframe. It puts pressure on the networking and storage technologies and the ability to deliver an efficient compute framework,” Bell said.

https://www.linux.com/topic/open-source/how-cern-using-linux-open-source/

Thanks to Linux for freedom and CERN uses protonVPN as thier internet services with Linux. CERN what ever we have find it is good , we need to stop it other wise Third Shaking of Planet is in full motion will be shaking planet so hardly.

Sorry if double posted, may have gone to parallel universe.

Why do satanists and devil-worshipping types do ritual black magick at cern?

Seems like all this particle physics is cover for inviting the false messiah to come to this dimension. Also seems like another money laundromat for satanic elitists.

I agree with .50cal.