In early October 2023, unusual tsunami waves were observed along parts of Japan’s coast — with reported amplitudes reaching roughly ~0.6 m in some locations — without the kind of single, large megathrust earthquake that normally explains Japan tsunami alerts. Instead, evidence points toward a rarer mechanism: rapid deformation linked to submarine volcanic/caldaera activity near the Izu-Ogasawara (Bonin) island arc.

Why this matters: it’s a reminder that “tsunami” does not always mean “megathrust rupture.” Some tsunami waves can be generated by non-seismic seafloor motion such as caldera uplift/subsidence, volcanic flank instability, or submarine mass movement. Related pillar: Submarine Landslides & Tsunami.

TL;DR — Japan’s October 2023 Tsunami (Non-Megathrust)

- Unusual tsunami waves were observed in Japan in October 2023, including reported ~0.6 m amplitudes.

- Unlike classic Japan Trench events, this episode was linked to a swarm of moderate earthquakes and possible submarine volcanic deformation.

- Post-event mapping indicates a new/modified submarine caldera near Sofu Seamount in the Izu-Bonin arc.

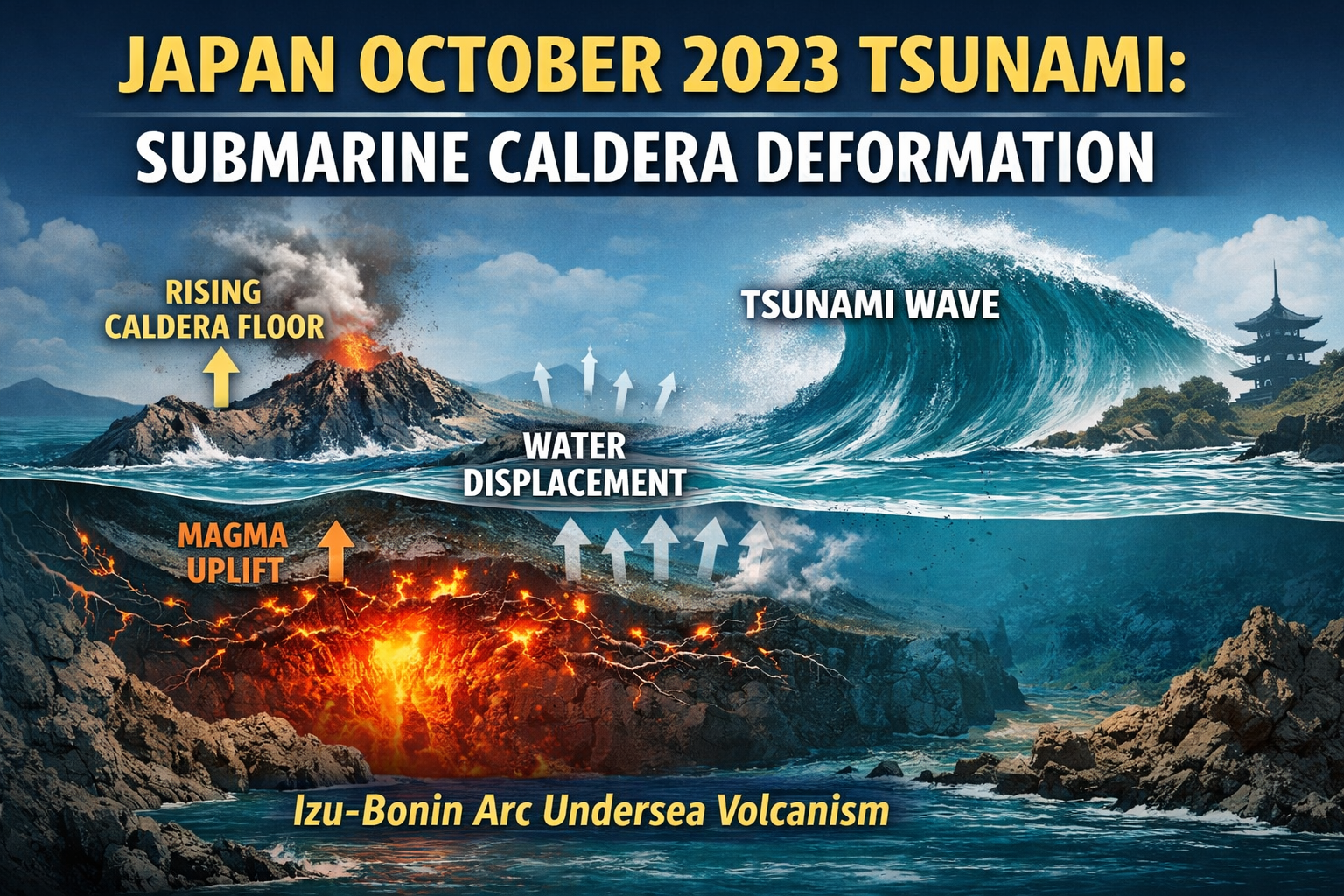

- Best-fit mechanism: rapid caldera floor uplift then subsidence (magma/hydrothermal pressure changes) displacing seawater.

- Takeaway: tsunami sources include more than megathrust earthquakes — monitoring must consider complex seafloor processes.

A New Submarine Caldera Discovery

Bathymetric surveys conducted after the October 2023 unrest revealed the formation (or major modification) of a submarine caldera in the vicinity of Sofu Seamount, west of Sofu-gan Island — part of the Izu-Bonin arc south of Tokyo. The caldera has been described as roughly ~2 km wide and ~400 m deep, consistent with a significant, rapid change in seafloor morphology during the episode.

Teams analyzing seismic waveforms and ocean-bottom data have suggested that vertical movements of the caldera floor (uplift followed by subsidence) — potentially driven by magma migration and/or hydrothermal pressurization — could have displaced enough water to generate the observed tsunami waves. This deformation occurred alongside a cluster of earthquakes recorded from October 1–8, 2023.

Tsunami Generation Without a Major Earthquake

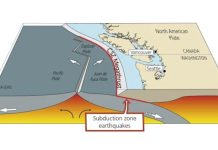

Classic Japanese tsunami scenarios are typically associated with a large megathrust rupture along subduction zones (e.g., Japan Trench, Nankai). The October 2023 episode was unusual because:

- It coincided with a swarm of moderate earthquakes (many in the M4–M6 range) and tremor-like activity, rather than one dominant rupture.

- On October 8, notable tsunami waves (reported up to ~0.6–0.7 m) were observed despite no single large earthquake matching the wave size in standard catalogs.

- Post-event bathymetry showed changes consistent with caldera-floor deformation near Sofu Seamount — pointing to a volcanic/volcano-tectonic source.

In other words: this does not behave like a classic trench-earthquake tsunami. It is better explained as a volcanogenic or volcano-tectonic deformation event that moved water through rapid vertical seafloor motion. For tectonic context, see Global Earthquake & Volcanic Zones.

How Caldera Movements Can Move Water

Submarine volcanic systems can generate tsunami waves when they cause fast vertical displacement of the seafloor. Near active seamounts, processes such as magma intrusion, hydrothermal fluid pressurization, and caldera floor uplift or collapse can displace large volumes of seawater.

In the October 2023 case, a key idea is that repeated uplift followed by subsidence — even over short vertical distances — can send pressure waves through the water column if the motion is rapid enough. Interpreted seismic signals are consistent with a relatively symmetric vertical deformation source, which fits a caldera-floor “piston” style mechanism better than a long, planar fault rupture.

This differs from tectonic tsunami generation, where the primary driver is sudden slip on a fault plane that displaces the seafloor over a large area. Here, the tsunami source is more localized and linked to volcanic system dynamics.

Implications for Japan’s Tsunami Hazard Profile

Japan is among the world’s most tsunami-prepared nations, largely because of well-known megathrust hazards along the Japan Trench and Nankai Trough. The October 2023 episode highlights that non-seismic sources — including submarine volcanic deformation — can also produce measurable tsunami waves.

While the October 2023 waves were relatively small (decimeter-scale) and caused no major damage, they reinforce three practical points:

- Volcanic and volcano-tectonic processes beneath the ocean can contribute to tsunami risk.

- Systems tuned mainly for megathrust earthquakes may miss or under-characterize volcanogenic tsunami sources.

- Ongoing bathymetric mapping, ocean-bottom sensors, and integrated seismic + hydroacoustic monitoring are essential for detecting complex sources.

What This Does Not Mean

- Not proof of an “imminent Japan megatsunami.”

- Not a classic Japan Trench megathrust signal.

- Not a reason to treat every tsunami as an earthquake rupture.

Frequently Asked Questions

Was the October 2023 tsunami in Japan caused by a major megathrust earthquake?

Evidence suggests it was not a classic megathrust tsunami. The episode coincided with a swarm and appears linked to rapid seafloor deformation near a submarine caldera in the Izu-Bonin arc.

How can a submarine caldera generate tsunami waves?

If the caldera floor uplifts or subsides rapidly (for example due to magma movement or hydrothermal pressure changes), it can displace seawater and create tsunami waves even without a single large earthquake rupture.

Is this the same kind of tsunami risk as the Japan Trench or Nankai Trough?

No. Japan Trench and Nankai scenarios are typically megathrust-fault tsunamis. This case is a non-earthquake tsunami mechanism that is generally more localized and linked to volcanic/volcano-tectonic deformation.

Should tsunami monitoring include volcanic sources?

Yes. While megathrust earthquakes remain the dominant risk, the October 2023 episode shows that volcanic and caldera-related seafloor motion can also generate measurable tsunami waves.

Where does this fit in the StrangeSounds pillar structure?

This is best treated as a case study under Submarine Landslides & Tsunami, with tectonic context provided by Global Earthquake & Volcanic Zones.