It began with a few small strange patches of slime, clinging to the rocks of the Heber River in Canada.

Within a year, the patches had become thick, blooming mats. Within a few years the mats had grown into a giant green snot. And within a few decades this snot had spread around the world, clogging up rivers as far away as South America, Europe and Australasia.

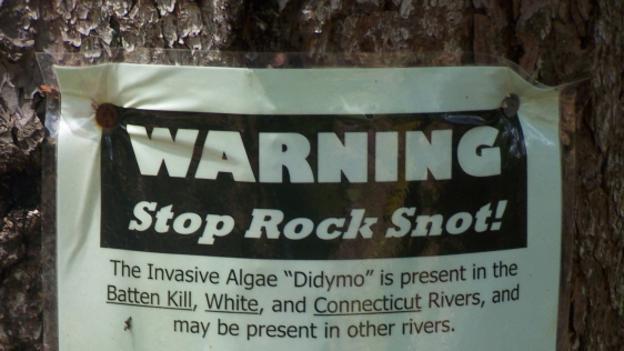

This snot, which is still flourishing today, is caused by a microscopic alga, a diatom that goes by its scientific name Didymosphenia geminata. It has become so notorious it has its own moniker, Didymo. People have been blamed for the sudden, global explosion of this tiny organism, unwittingly carrying the algae from river to river on fishing gear, boats and kayaks. The huge snots it forms have wreaked havoc in waterways, forcing governments and environmental organisations to initiate huge and costly clean-up operations.

But underlying the snots’ strange appearance is an even stranger story. About Didymo itself, about what it is, and how it behaves.

Scientists are now discovering that the sudden appearance of Didymo may not have been so sudden after all.

Its blooms aren’t really blooms – instead they are more of an elixir-induced metamorphosis. And Didymo seems to ignore the usual rules followed by invasive species. It even appears likely that this little diatom may not even be a significant problem itself; instead the green snot it forms may be a symptom of greater changes underway in freshwater systems around the world.

Malignant morphs

The diatom was first spotted in 1988, a few patches of alga within Heber River, in Vancouver Island, British Columbia. By 1989, several kilometres of river were covered in thick mats of the stuff, a surprise since the rare alga was not thought to grow this way. Today, Didymo coats the rocks of streams and rivers around the globe, from Quebec in Canada, Colorado and South Dakota in the US, Poland and Norway in Europe, even reaching Iceland, Chile and New Zealand.

Normally diatoms or other algae bloom when water is rich in nutrients, feeding an explosive increase in reproduction. This has a massive detrimental impact on freshwater systems. After diatoms increase in huge numbers, they also die in huge numbers, creating a surge in decay that depletes oxygen in the water. That suffocates freshwater animals such as insects, crustaceans and fish. Algal blooms essentially create an aquatic apocalypse.

But intriguingly, none of this applies to Didymo. When it creates huge snots, it’s not actually reproducing, scientists have discovered. Instead, it’s morphing, from something benign to something malignant. Each single-celled organism exudes long stringy stalks of mucous that entangle, creating the mats and snots that coat rocks.

“We usually think of massive cell division in a bloom,” says ecologist Cathy Kilroy, of New Zealand’s National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research Ltd, in Christchurch. “That’s not the case here.”

The water conditions which cause this transformation are also unexpected. “Most algal blooms are attributed to too much nutrients,” explains diatom researcher Sarah Spaulding, of the US Geological Survey in Colorado. “This is the first time it’s attributed to too little nutrient.”

Didymo, it turns out, only turns malignant when waters are very low in phosphorus, a nutrient often associated with pollution by detergents and fertilisers. It’s this paucity of phosphorous that causes the stringy stalks to grow, not the alga trying to reproduce, says Kilroy, whose experiments helped establish the connection.

This is a short video about didymo, an invasive species that has recently been found in the Youghiogheny River, and what you can do to help stop its spread:

Related to this discovery is an extreme irony. Governments and organisations around the world have, for a very long time, tried to stop algal blooms from strangling rivers by reducing phosphorous pollution, believing the algal feed off this nutrient boost. But in doing so, they might have encouraged the green snot that is Didymo.

“It goes against everything we’ve been thinking for 50 years,” says Spaulding.

Ever-present?

Didymo is also pulling a second surprise on scientists. For decades, it was thought that people spread the diatom around the world, the alga hitching a ride on the tackle, nets and wading boots of fishermen, and boats and boating equipment. To counter the threat, river users have been encouraged to clean their gear between visits.

But Didymo may not have been spread across the globe after all. It may have been there all along, believe Brad Taylor of Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire, US and Max Bothwell of Environment Canada’s Pacific Biological Station in Nanaimo, BC.

The two diatom researchers have just published a study in the journal BioScience. It reveals fossil and historical evidence that Didymo has long existed on every continent except Africa, Antarctica and Australia. Fossilised forms of Didymo, for example, can be found in at least 11 countries in Europe, across North America and Asia, and in South America.

“The idea that D. geminata is a recently introduced species or a native species expanding its range has been accepted and promoted,” say the scientists in their study. But that idea is wrong, they argue. And it explains why legislation banning certain types of wading gear, thought to help spread algae, has had no impact on the spread of Didymo’s green snot into new rivers. Because Didymo was already there.

There is one place that Didymo may have invaded; New Zealand. A decade ago, small patches of snot started appearing within rivers on South Island. The snots were suspiciously just downstream of places popular with fishermen and kayakers. It has since spread all over the island, green snots blanketing some river beds.

Catastrophic or not?

However, to fishermen and boaters wrestling with Didymo’s green snots, its origins are academic. They want to know what it’s doing to the waterways, whether it’s hurting fish or invertebrates such as the insects on which fish depend.

Even here though, the diatom continues to surprise. Research has shown that the alga boosts numbers of small insects, such as midges and gnats, while reducing numbers of larger insects, such as mayflies, stoneflies and caddisflies. “That seems to be a universal change in these streams,” says fisheries biologist Daniel James of the US Fish and Wildlife Service in the Black Hills of South Dakota, where Didymo appeared in 2002.

James’s research has focused on the diets of freshwater fish, and whether they have less to eat due to the presence of green snots. But the reduction in larger insects hasn’t so far caused a problem, as the fish are just eating more of the smaller insects.

While the fish of South Dakota seem unaffected by Didymo, which covers around a third of the riverbeds studied by James, he cautions that may not be so in other places, such as in New Zealand. There the snots can blanket the whole river.

However, on the whole, Didymo doesn’t yet seem to have caused the ecological catastrophe that so many feared. “At first there was a huge concern about how Didymo was going to affect fish,” says James. “But it’s more of an annoyance.”

It can cause some problems for irrigation systems, says Kilroy. But its biggest impact seems to be aesthetic. “The main effect of Didymo is how it changed the appearance of rivers and streams,” she says. “It’s not toxic. It really doesn’t do anything really awful.”

The real invaders

So what then, is the real meaning of the Didymo phenomenon worldwide? The true significance of the green snot taking over the world’s rivers may not be the snot itself, but what it tells us about our own, human impact on freshwater ecosystems.

Bothwell, Taylor and Kilroy have collaborated on new research recently published in the journal Diatom Research. They propose a few mechanisms by which humans may have altered the world’s rivers, creating the opportunity for Didymo.

First, the burning of fossil fuels such as oil and coal has increased the amount of nitrogen compounds on the atmosphere. That nitrogen causes soil organisms to better use phosphorous in the soil, meaning less phosphorous runs into rivers and streams. That creates the more phosphorus-free water beloved by Didymo.

A second mechanism, which has the same effect as the first, is the increasing addition of nitrogen-rich fertilisers to soils by agriculture and forest managers.

A third involves climate change, and the way it changes the timing of growing seasons and melting of snow. This might somehow also reduce the amount of phosphorous entering freshwater ecosystems, the researchers say, again creating the environment in which Didymo green snots can flourish.

It could be that different mechanisms are the cause of Didymo blooms in different places around the world, or that they are working in synergy.

But whichever turn out to be at work, the research seems to suggest that we have met the invaders, and they are not green snot-causing Didymo diatoms. They are us.