A recent deep ocean mapping survey has learned that a geologically-active strip of seafloor called the Cascadia Subduction Zone is bubbling methane like mad.

It could be one of the most active methane seeps on the planet.

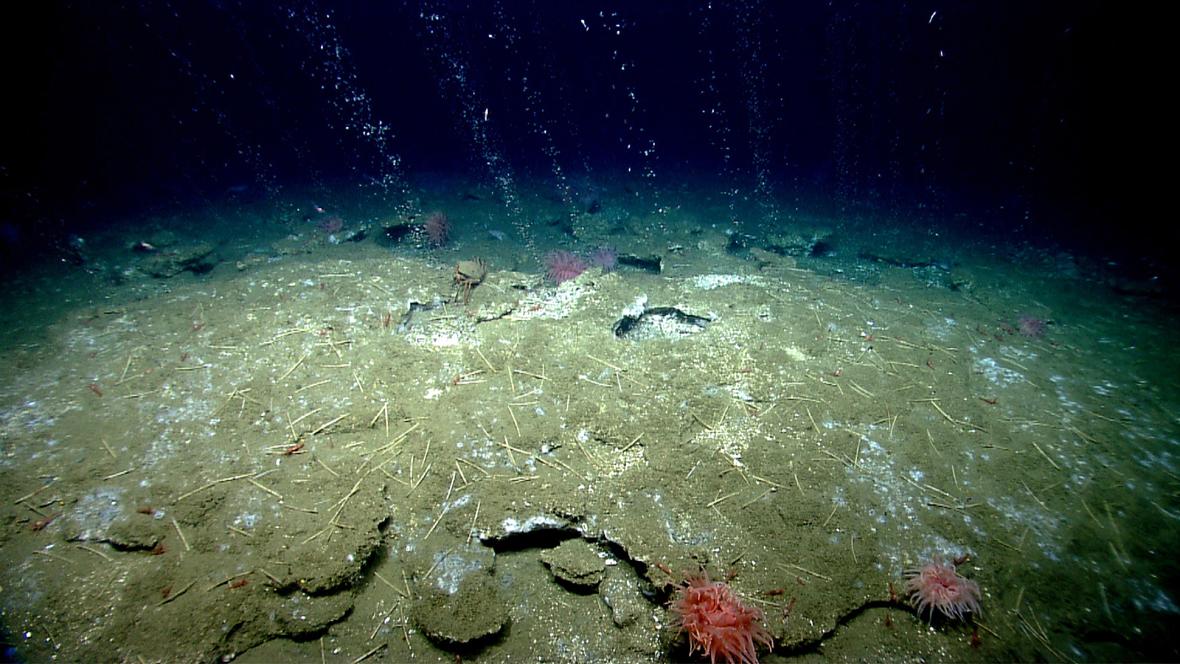

“It’s like bottles of champagne all along the seafloor,” said Jesse Ausubel, an organiser for the 2016 National Ocean Exploration Forum, where the gaseous discovery, along with other intriguing finds from recent deep ocean surveys, is being presented this week.

For years, scientists have been aware that methane, an odourless, colourless gas bubbles up from the seafloor where the conditions are right. Recent scientific surveys have discovered hundreds of methane seeps along the Atlantic continental margin, and it’s believed there could be thousands more across the world.

Understanding these seeps is a hot topic in Earth science research today, given that methane is a potent greenhouse gas. In fact, many scientists worry that by warming the oceans, climate change is speeding up the very processes that produce methane, in addition to melting icy methane hydrates that accumulate on the seafloor. In theory, this could lead to an enormous release of heat-trapping gases to the atmosphere.

But the question of what’s rare and what’s common is wide open. The basic geologic map of the seafloor remains to be made.

A NOAA-led survey of the Cascadia Subduction Zone, performed by the E/V Nautilus over the winter, was a first attempt to get a handle on how much natural methane seepage is occurring over this geologically-active area. Although the ROV only mapped a small fraction of the subduction zone in detail, it identified some 450 individual bubble streams, which nearly doubles the number of methane vents that have been spotted along US coastlines.

Washington University oceanographer Paul Johnson, a collaborator on the survey, called the finding a “very significant discovery”, adding that there are likely a lot more methane plumes that E/V Nautilus missed. “The capability to image methane bubble streams in the water column is relatively new, so it is fair to say that the more we look, the more we find,” he said.

Whether this giant methane seep could be contributing to our climate problem remains to be seen, but it’s a question that merits further study.

We still don’t have a good sense of whether the methane seeps are continuous, like natural gas running out a pipe, or more intermittent and dependent on seafloor conditions. We also don’t know how much of the methane actually escapes to the atmosphere.