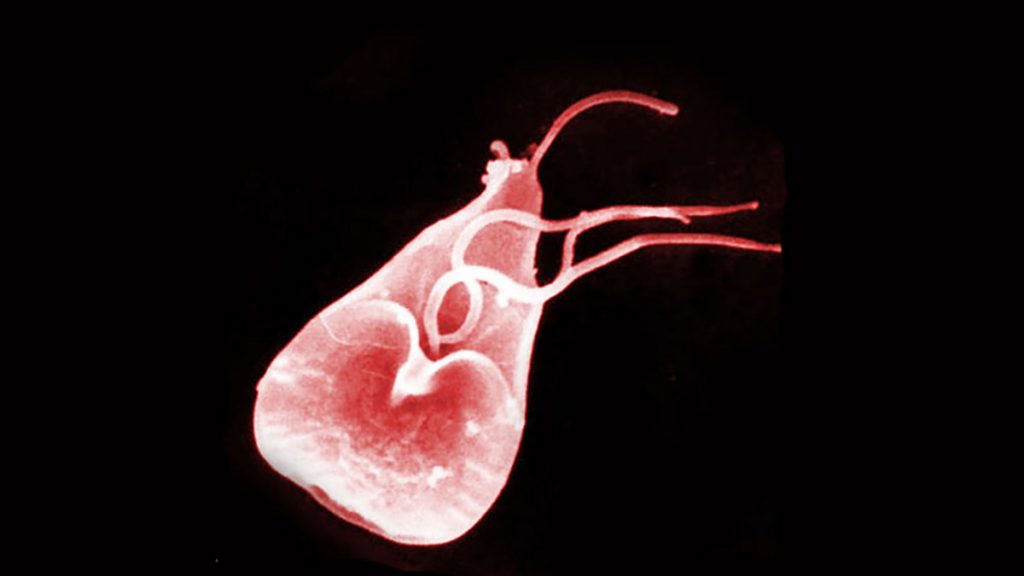

Last year, a good friend of mine caught chronic giardiasis. The diarrhea that resulted was unpredictable, frequently sending him scrambling for a bathroom. For most of the year, that meant his dating life was totally on hold and he couldn’t travel. Already a thin guy, the resulting weightloss caused him to look visibly ill. To him, the worst part was the embarrassment all this caused, all from a parasite he caught on a camping trip here in California.

Which is why I want to address a story that ran last week. Writing in Slate, Ethan Linck rehashed an eight-year-old study that found that contaminants in backcountry water sources are exceedingly rare. Using that evidence, he argued that you don’t need to clean water on camping trips in the U.S. and Canada. “The idea that most wilderness water sources are inherently unsafe is baseless dogma, unsupported by any epidemiological evidence,” Linck claims. He goes on to suggest that the outdoor recreation industry has pushed sales of water filters in order to sell campers on added complication they don’t need. He says he long ago stopped purifying his own drinking water while camping.

The study Linck cites reaches similar conclusions: “There is no good epidemiologic evidence that North American wilderness waters are inherently unsafe for consumption,” author Thomas R. Welch argues. The study tested a water source in a high-use area in the Sierra Nevada mountains, in central California — the kind of place you’d expect to find contaminants. Researchers found only trace amounts of giardia there: one would have to drink more than seven liters of the water to get sick, they said. In other, less frequently used areas, the study found no harmful bacteria or protozoa.

There are a few very obvious problems with all this:

- While it’s correct that there is little scientific evidence of significant pathogens in wilderness water sources in the U.S. and Canada, there’s also very little scientific study on the subject. The most thorough research cited by Welch appears to have been conducted two decades ago by the editors of Backpacker magazine.

- Not all backcountry water sources are created equal. Welch’s work relies on water testing conducted only in a single highly-protected mountain range in a single highly-regulated state— California’s Sierra Nevada. Do studies conducted there translate to Minnesota’s Boundary Waters, or Georgia’s Okefenokee Swamp? To suggest that they might is ridiculous. It’s also worth noting that pathogen levels are constantly in flux—variables like rainfall, temperature, season, and animal behavior all play a role. The level of pathogens recorded at a single water source will vary month-to-month and year-to-year.

- The study makes no account for how different people recreate outdoors and how they define that recreation. “Backcountry” may mean the High Sierra to Linck, Welch, and me, but something else entirely to a Cub Scout troop on the East Coast. As Welch details in his study, water sources adjacent to a sewer outlet have plenty of documented cases of spreading pathogens.

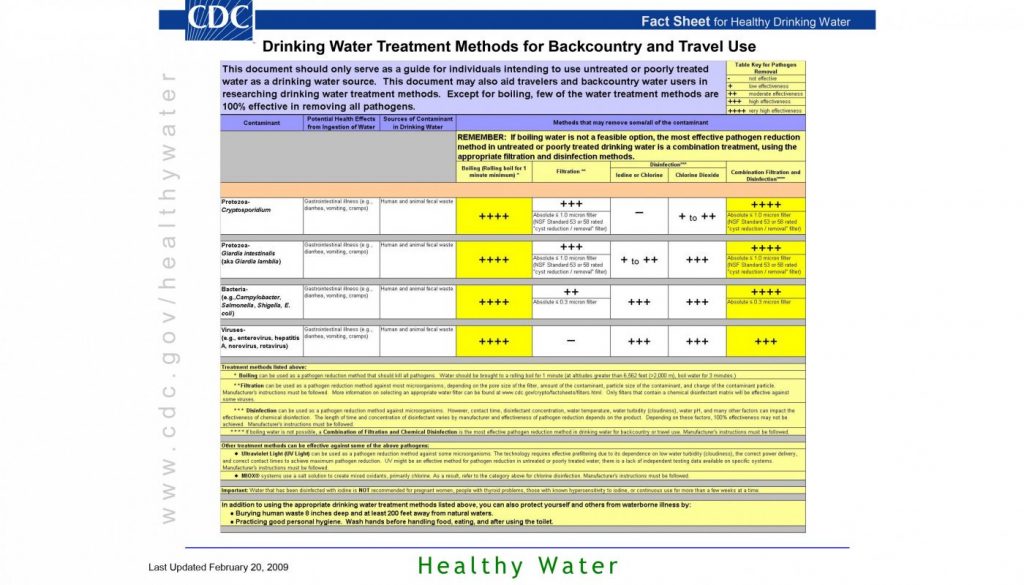

- Linck’s assumption that cleaning backcountry water requires a “$99.95 microfilter pump” is simply wrong. Cheaper, simpler methods can actually be more effective, and don’t place a heavy financial or weight penalty on the user. Simple Potable Aqua Chlorine Dioxide Water Purification – Portable Tablets For Camping or Emergency Drinking Water

will kill any protozoa, bacteria, cyst, or virus you’ll find in North America, and cost around 50 cents a tablet. Boiling water is free, if you have a stove, and 100 percent effective.

- The low rates of infection reported by Welch’s study don’t control for whether or not any water purification methods were used by the study group. As Linck argues, virtually every backpacker is using a purification method of some kind, so the reported infection rates are misleading in this context. The low rates of infection reported could actually be a strong argument for the use of purification techniques and products.

Together, those issues create a highly misleading and arguably irresponsible conclusion. There is not sufficient scientific evidence to tell people not to filter their water—only enough to prove that some water sources in the Sierra Nevada may be safe to drink without treatment.

The irresponsibility of the don’t-filter argument is exacerbated by two things:

- While most giardia, e. coli, cyrptosporideum, and waterborne pathogens induce fairly minor illnesses in adults, the effects can be much more severe if the infected person suffers from immunosuppression, is very young or old, or, as with my friend, is simply unlucky. In children, for instance, the CDC says giardiasis can may lead to symptoms as severe as delayed physical and mental growth, slow development, and malnutrition.

Effective treatment options are affordable and easy to use. Use an expensive filter because you’re short on time or like cleaner tasting water—cheaper methods will keep you just as healthy. - Both Welch and Linck argue that the failure to wash hands after taking a poo is responsible for more infections than drinking unpurified water. But while that is an argument for taking some hand sanitizer along, it is not an argument against water treatment.

The next time you go camping, you should do both.

[…] Last year, a good friend of mine caught chronic giardiasis. The diarrhea that resulted was unpredictable, frequently sending him scrambling for a bathroom. For most of the year, that meant his dating life was totally on hold and he couldn’t travel. Already a thin guy, the resulting weightloss caused him to look visibly ill. To him, the worst part was the embarrassment all this caused, all from a parasite he caught on a camping trip here in California. Read More… […]

[…] post You Really Should Filter Your Water appeared first on STRANGE SOUNDS – AMAZING, WEIRD AND ODD […]

[…] post You Really Should Filter Your Water appeared first on STRANGE SOUNDS – AMAZING, WEIRD AND ODD […]