Despite recent panic surrounding the potential reversal of our planet’s magnetic poles, new evidence suggests it’s probably not the impending doom it sounds like. Implausible as it sounds, public worry about the poles flipping seems to be ever-present, typically backed by real evidence of the Earth’s magnetic field weakening. These outbreaks of concern almost always come with doomsday threats. But really, you don’t have to worry.

It turns out that the current behavior of the field “is not characteristic for the beginning of a reversal or excursion,” i.e., a quick position change to the field’s poles, study author Monika Korte from the German Research Centre for Geosciences told Gizmodo.

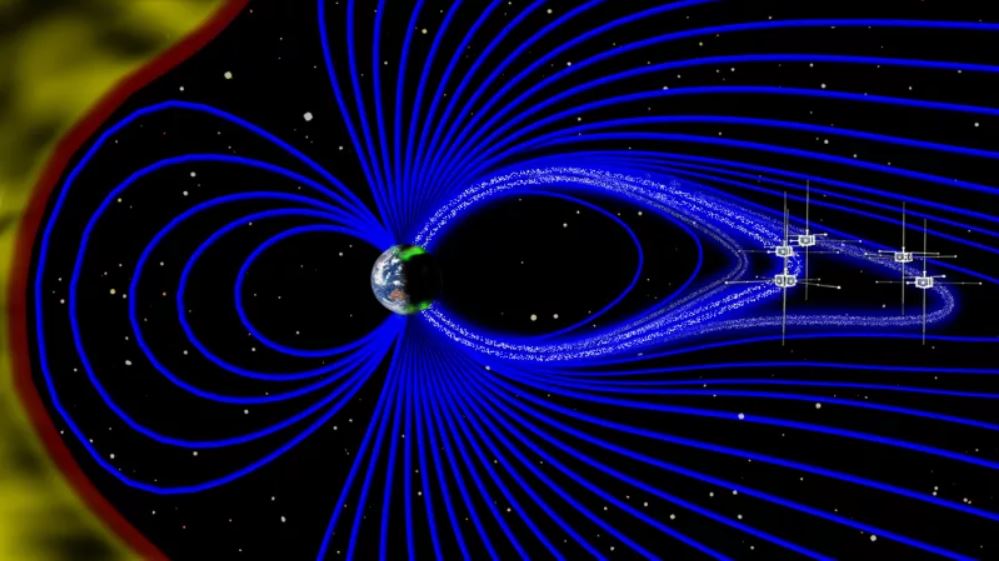

The Earth has a magnetic field, generated (we think) by motion in its core. A recent book and the subsequent press coverage mention that the field’s poles have flipped hundreds of times in Earth’s 4-billion-year history, but haven’t done so in almost 800,000 years. The field has been weakening around 5 percent per century since 1840 and is especially weak in the South Atlantic. Some think this could signal an impending flip, which could herald mass extinctions and power outages.

The authors behind the new paper found two times in the Earth’s geologic history where its magnetic field looked similar to the way it does today, based on past data. It had big spots of weaker field, like the one over the South Atlantic. Both times, the poles didn’t switch, nor did they experience an excursion where they quickly snap to a different position, according to the paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

That being said, if the South Atlantic magnetic field anomaly persists, and if the field continues to weaken, it could still be bad for electrical grids or satellites passing overhead. We humans still rely on the magnetic field as protection from high-energy radiation from space.

Others agreed with the paper’s importance and conclusions. “The analysis shows that the magnetic field showed similar structures in the past that did not lead to an extreme event, so the South Atlantic Anomaly cannot be taken as an indication that we are in the early stages of such an event,” Sanja Panovska, another researcher at the German Research Centre for Geosciences who was not involved in the study, told Gizmodo.

As with any research based on modeling, there are limitations, such as missing data. “Although it is the first model using a reasonable data coverage, there are still large gaps in global data coverage with palaeomagnetic sediment records that intrinsically limit our knowledge about the global field behavior,” said Panovska. And given that this is a model, the Earth may not behave the way scientists expect.

But you still shouldn’t worry about the magnetic field flipping. As Nadia Drake writes for National Geographic, it’s a process that occurs on incredibly slow timescales, thousands of years or so. We don’t even have proof that such a reversal would lead to mass extinctions, either.

So, as usual, the end is not imminent. That goes for civilization in general, of course, since you’re probably not living past 120.