The U.S. military on the Japanese island of Okinawa is facing accusations of environmental contamination after high levels of a carcinogenic chemical were found in the rivers around a U.S. air base and in the blood of local residents.

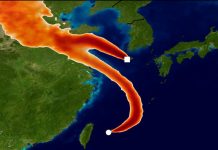

The controversy is inflaming an already sensitive situation for the U.S. military in Okinawa. The island is home to half the 54,000 U.S. military personnel in Japan and has the largest U.S. air base in the Asia-Pacific. The military presence, however, is widely unpopular.

The accusations have hit the front pages in Okinawa and been raised in a parliamentary environmental committee in Tokyo just before President Trump arrives for a state visit, although it is unlikely to be an issue either the U.S. leader or Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe will want to address.

It also mirrors wider concerns in the United States about contamination from a family of industrial chemicals known as perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS).

The chemicals have a wide array of consumer and industrial uses, including in nonstick cookware and firefighting foam, but do not break down in the environment. They are the target of congressional bills that would require stronger action to regulate their use and to decontaminate water supplies around the United States.

In Okinawa, a study by two Kyoto University professors found high concentrations of a chemical called perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) in rivers passing through and around the Kadena Air Base and the Marine Corps Air Station Futenma.

PFOS is a chemical in the PFAS family and was used by the U.S. military as an ingredient in firefighting foam for five decades until 2015, along with perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA).

Air Force Col. John Hutcheson, director of public affairs for U.S. Forces Japan, said the chemicals had been used for fighting petroleum fires primarily at military and civilian airfields — and in a number of industrial processes — because they help rapidly extinguish combustion, protecting personnel and property.

“U.S. military installations in Japan are transitioning to an alternative formula of aqueous film-forming foam that is PFOS free, only contains trace amounts of PFOA and meets military specifications for firefighting,” he said.

Regarding the accusations of environment damage, however, the spokesman declined to comment.

“We have seen press reports but have not had a chance to review the Kyoto University study, so it would be inappropriate to comment on its findings,” Hutcheson said.

The use of PFOS and PFOA is in principle prohibited in Japan and was also phased out in the United States in recent years after studies linked the chemicals to cancer, thyroid disease, weakened childhood immunity and other health problems.

Professor Emeritus Akio Koizumi and Associate Professor Koji Harada found concentrations of PFOS at four times the national average in the blood of Okinawans living near the U.S. bases on the island.

Their study was conducted jointly for Kyoto University, a Kyoto medical association and a hospital in Okinawa but has not been peer reviewed.

Koizumi and Harada said it was not clear how the contamination was affecting residents’ health but said it was evident that tap water had been contaminated.

“The source of the contamination may be on-base compounds, and it is important for this to be strictly controlled under domestic law,” they wrote.

Tomohiro Yara, an opposition member of parliament from Okinawa and a former journalist, says he has asked Kadena Air Base for a response but has not received one. “We don’t know why the substance is found in rivers outside the base, but we know it’s used within the base,” he said. “Despite that, nobody has responded. This is outrageous.“

Japanese Environment Minister Yoshiaki Harada says it is a “serious issue” and has promised an investigation.

“To begin with, I think it is a problem for the issue not to be addressed for as long as three years,” he said in response to Yara’s question. “We as the government take the issue seriously and will begin with an investigation.” Only after that investigation would the government talk to the U.S. military about the issue, he said.

Jiro Fukuhara, a civil engineer in the water management section at the Okinawa Prefectural Government, said the government thinks there is a “high probability” the Kadena Air Base is the source of the contamination but said local water sources are being treated, a process that he said has brought tap water within safe levels.

In 2016, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency established a lifetime health advisory level of 70 parts per trillion for PFOS and PFOA in drinking water.

Hutcheson said the Okinawa Prefectural Enterprise Bureau provides the drinking water used at Marine Corps Air Station Futenma. “PFOS and PFOA have not been detected in drinking water on MCAS Futenma at levels above the U.S. EPA lifetime health advisory,” he said.

But Fukuhara said that since 2016, local authorities have asked in vain that the Ministry of Defense get permission from the U.S. military for them to inspect the Kadena Air Base to investigate the source of the contamination.

Yara said it appeared that neither Japanese domestic law nor U.S. law regulating PFOS was being applied.

“That means there is no law within the base,” he said. “To the extent they are provided with the land, the airspace and the environment by local people, they should use them properly. If they contaminated it, they should say ‘We are sorry.’ ”

The PFAS group is sometimes known as “forever chemicals” because the substances do not break down naturally and are thought to be in the bodies of nearly every American and others with long-term exposure.

PFOS and PFOA have been replaced in recent years with other PFAS with slightly different chemical compositions. But the Environmental Working Group, a U.S.-based nonprofit organization, says the effects of the replacement chemicals have never been properly tested.

A study EWG released this month in conjunction with the researchers at Northeastern University found PFAS contamination at 610 sites in 43 U.S. states. The sites include drinking water systems serving an estimated 19 million people.

In a February referendum, Okinawa voters expressed resounding opposition to plans to build a new U.S. military base on the island, but the results have been ignored by the Japanese government and U.S. military, which say they will move ahead.

Big troubles in sight here too!

Follow us on FACEBOOK and TWITTER. Share your thoughts in our DISCUSSION FORUMS. Donate through Paypal. Please and thank you

[WP, RyuKyu Shimpo]