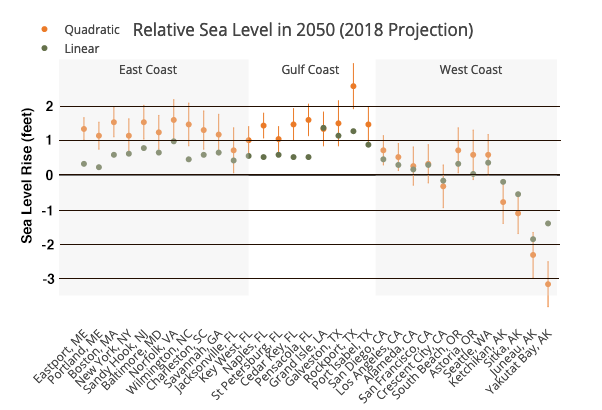

Texas and Louisiana have the highest rates of sea level rise in the U.S., with Grand Isle, Louisiana (7.75 mm or 0.305 inches per year) topping the list, according to the annual sea level “report card.” Rockport, Texas (south of Galveston) had the highest acceleration rate (0.240 mm/year2), due to rising seas combined with subsiding land, caused by such things as natural geological processes, ground water pumping, and oil industry activity.

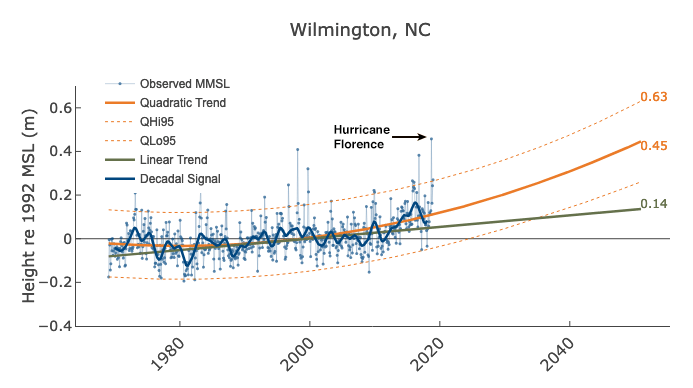

Many sea level rise predictions rely on observations of current sea level rise (currently about 3.1 mm/year globally) to project future water levels. However, the researchers argued that since sea level rise is accelerating, a more valid forecast can be made by assuming the current acceleration rate will continue through 2050. Research published in 2018 found that global sea level rise has accelerated by 0.084 mm/year2 over the past 25 years, and 18 of the 32 U.S. tide gauges from the sea level report card had acceleration rates greater than the global average.

If Rockport’s observed 2018 acceleration rate were to hold, the sea level report card predicted 0.78 meters (2.6 feet) of sea level rise by 2050, relative to 1992 levels—the highest predicted rise of any of the 32 locations studied. Predicted sea level rise at all other stations on the Atlantic coast, based on current rates of acceleration, ranged from 0.7 to 1.6 feet. Predicted rises along the Pacific coast were lower, ranging from -0.3 to 0.7 feet from California to Washington. Relative sea level is falling everywhere in Alaska, due to crustal rebound from melting glaciers.

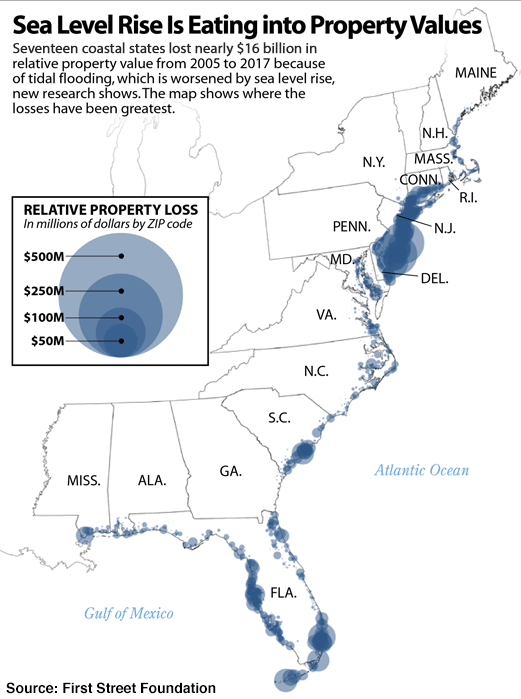

Coastal flooding is erasing billions in property values from sea level rise

A February analysis by First Street Foundation, a non-profit focused on creating awareness on the economic dangers of climate change-enhanced high tide flooding, estimated that property value losses from coastal flooding in 17 states from Maine to Mississippi were nearly $16 billion from 2005 to 2017. Florida, New Jersey, New York and South Carolina, with more than $1 billion in losses, topped the list. The actual losses are probably higher, since their model did not include losses from hurricanes or heavy rains. As explained in an excellent article by Neil Katz at weather.com, the losses do not represent actual depreciation in real estate values, which are still increasing in coastal areas subjected to high tide flooding. What’s being estimated are potential increases since 2005 that were never realized. Increasingly flood-prone coastal areas are rising in value more slowly than adjacent areas that do not flood. The article also detailed the aggressive actions cities like Ocean City, MD, and Miami Beach are taking to stay ahead of sea level rise.

But even the most aggressive actions to adapt to sea level rise currently being taken in low-lying U.S. cities on the Atlantic Ocean may be insufficient to prevent a collapse of their real estate market in the long term; much greater investments are needed. Jeff Goodell’s must-read 2017 book on sea level rise, The Water Will Come: Rising Seas, Sinking Cities, and the Remaking of the Civilized World (our review here), offers two scenarios on what might happen in Miami as sea levels continue to rise due to human-caused climate change:

“In a winning scenario, civic leaders address the risk or sea level rise in a proactive way, lobbying hard for state and federal funds and demonstrating enough political courage to raise taxes so that the city will have the money to elevate streets and causeways, invest in better sewer systems, and keep the low-lying airport functioning smoothly. Foreign investors don’t panic, property values don’t plummet. Population declines and some buildings are abandoned, but innovation flourishes and new ways of living with water emerge—houses float, canals replace streets, rooftops host gardens. The water keeps rising and people keep leaving, but it is a slow, stable retreat buffered by waves of innovation and civility.”

“In the losing scenario, the more investors understand the risk of sea level rise to buildings and infrastructure, the less willing they will be to invest in the region. As people sell, the supply of houses and condos rises and prices fall. Property tax revenues decline. Even a modest drop has enormous consequences for the city and county budgets. This means cuts in teachers and cops and firefighters, but it also means less money to buy pumps, fix roads, build seawalls, and build and maintain all the other infrastructure needed to deal with rising seas. Instead of having the courage to raise taxes to make up for the shortfall, politicians, fearful of spooking the market further, fight to keep taxes low. With no money for repairs or upgrades, infrastructure crumbles. And that, in turn, causes more people to sell, and the downward spiral continues. People with money leave, pirates and con artists arrive. Instead of innovation and civility, you get crime and lawlessness. Long before Miami is the New Atlantis, it will be broke and waterlogged and full of half-abandoned neighborhoods where mosquitoes breed and leaking septic systems turn Biscayne Bay into an algae-filled lagoon.”

Analysis

Most low-lying coastal cities will face similar scenarios in the coming decades, as competition for state and federal dollars to adapt to sea level rise intensifies. Ultimately, we will be forced to abandon much of the coast, particularly in non-urban areas, since there will not be enough money to defend thousands of miles of coast. The richest cities with the most political power will fare the best.

The only answer to rising seas is to retreat, an October 2017 op-ed in The News & Observer (Raleigh, North Carolina) by two of the authors of the excellent 2017 book, Retreat From a Rising Sea, Dr. Orrin Pilkey and Keith Pilkey, summarized what we need to do to adapt to rising seas. None of these are on anyone’s to-do list, they argue:

▪ Do not build any more large buildings in beach communities as these structures reduce the flexibility of a community’s response to sea level rise.

▪ Do not rebuild storm-damaged buildings.

▪ Move or demolish buildings that interfere with beach processes, such as the seasonal changes in beach shape.

▪ Do not allow beach nourishment to be the justification for increasing the density of development as this only promotes putting more buildings at risk.

▪ Do not build seawalls if you want a beach for future generations.

▪ Plan now for retreat.

In their book, they say: “Like it or not, we will retreat from most of the world’s non-urban shorelines in the not very distant future. Our retreat options can be characterized as either difficult or catastrophic. We can plan now and retreat in a strategic and calculated fashion, or we can worry about it later and retreat in tactical disarray in response to devastating storms. In other words, we can walk away methodically, or we can flee in panic.”

To give us a fighting chance of avoiding the “flee in panic” scenario, we need to reform the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP). The program is $20.5 billion in debt, even after cancelling $16 billion in debt after the hurricanes of 2017 (Harvey, Irma, and Maria.) NFIP encourages building in risky areas, and its premiums need to reflect the true risk of living on the coast. NFIP reform needs to be done carefully, though, since if insurance rates rapidy increase in high-risk areas, an economically devasting collapse of the real estate market might result.

A 2017 NRDC analysis found that 0.6% of the 5.1 million properties insured by NFIP accounted for a disproportionate 9.6% of all damages paid between 1978 and 2015, totaling $5.5 billion. The process to buy out such repetitive-loss properties needs to be accelerated. According to the head of NFIP, from 1989 to 2017, FEMA spent $3.1 billion to buy out 45,000 repetitive-loss properties, which they estimated would prevent $6.5 billion in losses. The NRDC report outlines tens of billions in savings that NFIP could realize in coming decades by buying out an additional 0.5 – 1.6 million flood-prone properties.

It is welcome, then that bipartisan legislation was introduced on March 8 in the U.S. House of Representatives to establish a fund to provide low-interest loans to help property owners better flood-proof their homes and businesses. Those that do so would get a reduction in their NFIP flood insurance premiums. The State Flood Mitigation Revolving Fund Act of 2019 is designed to drive down flood insurance premiums and ultimately reduce post-disaster claims and recovery costs. According to a 2018 report by the National Institute of Building Sciences, for every dollar spent on hazard mitigation, the nation saves $6 in post-disaster costs.

So get prepared and you will get cash from the government!