May 18, 2021 marks the 41th anniversary of the Mount St. Helens eruption, which reverberated throughout the Pacific Northwest and around the world.

The next eruption near a Cascade volcano could upset the lives of hundreds of thousands of people and disrupt many others.

The nation’s wake-up call

On March 20, 1980, a strong earthquake shook the slopes of a picture-perfect, snow-capped mountain in the Cascades Range.

In the video above, USGS scientists recount their experiences before, during and after the May 18, 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens. Loss of their colleague David A. Johnston and 56 others in the eruption cast a pall over one of the most dramatic geologic moments in American history. Stephen M. Wessells, U.S. Geological Survey (Public domain.)

The earthquake was recorded by seismometers installed by a group of University of Washington and USGS scientists, who were studying geothermal resource potential in the area.

The earthquake was the first of an intense sequence of earthquakes that were unusual for the Pacific Northwest. Their location directly beneath the volcano was immediately recognized as a possible symptom of an impending eruption.

If the mountain did become active, what would happen? Although no one knew it then, that was the beginning of the Nation’s wake-up call to the presence of true volcanic hazard in the Pacific Northwest.

The mountain is Mount St. Helens. As the world later watched, that strong earthquake was followed by many earthquakes as magma forced its way upwards, bulging the north flank of the volcano and forging a path to the surface with every earthquake and small steam-and-ash explosion.

Less than two months later, the mountain gave way with a tremendous landslide and lateral blast, resulting in the loss of 57 lives and property damage and destruction totaling over a billion dollars.

The Mount St. Helens eruption in 1980 ranks among the most significant geologic events of the 20th century for both the United States and the world.

Occurring near populated areas and in the age of television, people throughout the United States and around the globe were captivated at images of the volcano’s catastrophic eruption, the devastation, and the stories of impacted lives.

Mount St. Helens is an especially dangerous volcano

In the mid-1970s, USGS geologists Dwight R. Crandell, Donal R. Mullineaux and others roved the slopes of Mount St. Helens, investigating the lava flows and layers of ash and pumice that revealed a story of a frequently active and at times highly explosive volcano.

A hazards report prepared in 1978 suggested Mount St. Helens could be an especially dangerous volcano because of its past behavior.

In 1980, as earthquakes intensified, USGS scientists from Hawaii, Alaska, California and Colorado descended on Mount St. Helens, joining forces with scientists at the University of Washington who had detected the initial earthquakes and sounded the early alarm.

The rate of changes at the volcano required around-the-clock work both in the field at observation posts like Coldwater I and Coldwater II, and at U.S. Forest Service headquarters in Vancouver, Washington.

The media, public officials, first-responders and land managers were updated daily about events at the volcano.

There was no formal Cascades Volcano Observatory and no dedicated office space. Instead, scientists staged their volcano monitoring program within an operations center established at the U.S. Forest Service headquarters in downtown Vancouver, Washington.

Just as it appeared that unrest at Mount St. Helens was diminishing, the north flank of the volcano failed.

On May 18, 1980, the bulge slid into the valley and uncorked a catastrophic lateral blast. In total, the top 1,300 feet of the mountain was removed.

At a speed of more than 300 mph, the blast flattened 230 square miles and reached 17 miles northwest of the crater.

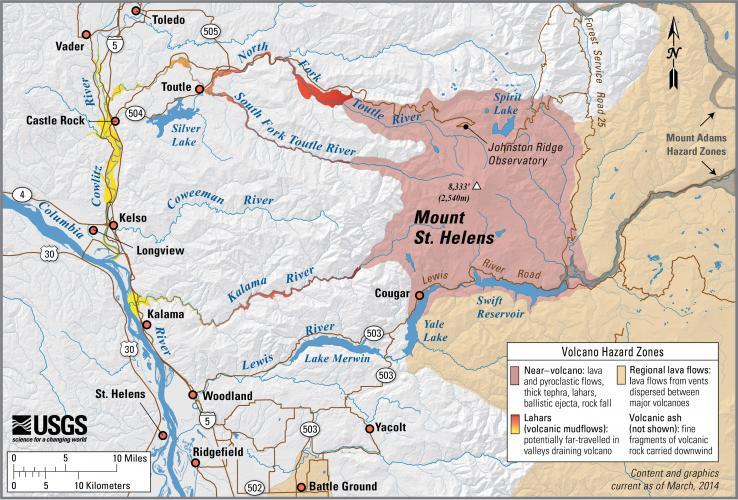

Lahars (volcanic mudflows) inundated valley floors and carried sediment as far as Columbia River.

Fifty-seven people, along with countless wildlife and fish populations, died in the eruption.

USGS scientist David Johnston was caught up in the blast, even though he was at a distance presumed relatively safe at the time.

The beginnings of CVO

What would the volcano do next? During the summer of 1980, explosive eruptions sent ash to nearly all four corners of Washington State and beyond.

Within the crater, a new dome began forming, producing a new set of hazards stemming from the possibility of dome collapse.

The USGS took on the role of lead Federal agency responsible for providing reliable and timely warnings of volcanic hazards to state and local authorities, eventually moving out of the joint field office operated with the U.S. Forest Service and establishing a permanent regional office at Vancouver, Washington, an office that was officially dedicated on May 18, 1982.

The Cascades Volcano Observatory (or CVO), as it was named, was dedicated in David Johnston’s memory and sought to ensure that future volcanic activity in the Cascades Range would come as no surprise to the region and that people would have as much time as possible to prepare.

Throughout the next 35 years, the CVO has progressively expanded its monitoring and study of other volcanoes of the Cascades Range.

Nevertheless, Mount St. Helens has continued to be a focus of the new observatory, as eruptions continued throughout much of the 1980s and again in 2004-2008 during a renewed period of dome building eruptions.

The next eruption near a Cascade volcano could upset the lives of hundreds of thousands of people and disrupt many others.

Fortunately, volcanoes tend to give warning signs that they’re getting ready to erupt, and CVO scientists keep ever-vigilant to make sure that residents of the Pacific Northwest have as much warning as possible before an eruption.

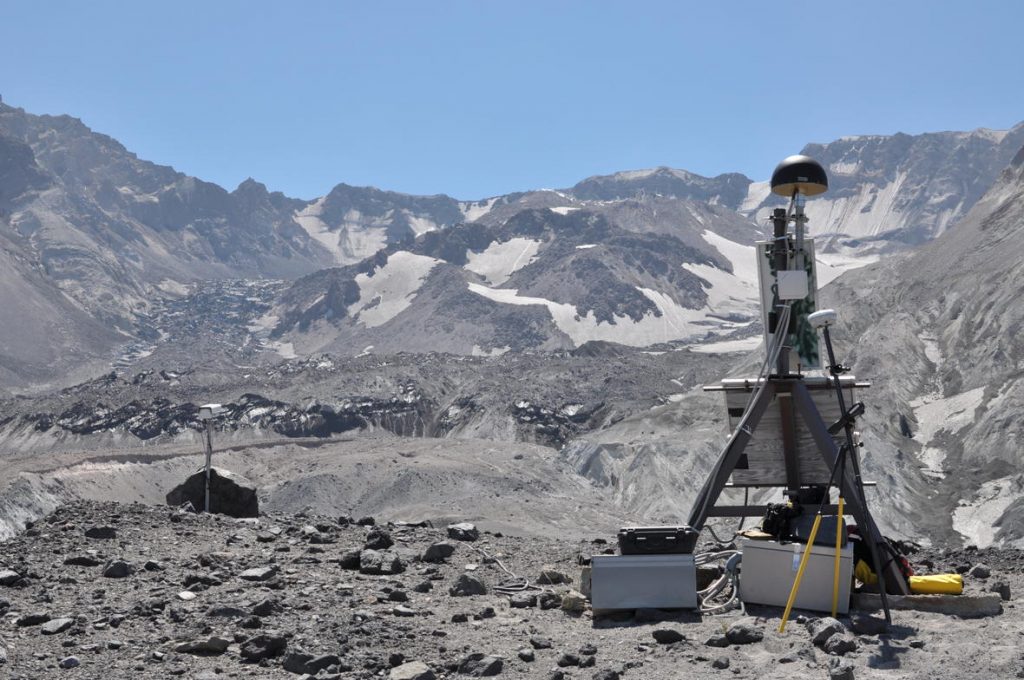

During the past decade at CVO, USGS and the Pacific Northwest Seismograph Network have expanded monitoring networks on Mount St. Helens, Mount Rainier, Mount Hood, Three Sisters, Newberry Volcano, and Crater Lake. Although they are often located in hard-to-access places, you still might see these instruments on a volcano’s slopes. [USGS]

Although the Cascade volcanoes currently slumber, it is only a matter of time before one reawakens. So be ready, get prepared and watch this excellent documetary about volcanism and earthquake in this dangerous part of the U.S. (click on the picture below).

Which Cascades volcano is going to erupt next? Please tell me I want to get ready and survive…

Now subscribe to this blog to get more amazing news curated just for you right in your inbox on a daily basis (here an example of our new newsletter).

You can also follow us on Facebook and/ or Twitter. And, by the way you can also make a donation through Paypal. Thank you!

I remember Harry R. Truman, the ‘old man on the mountain’, lots of stories about him at the time before the eruption. I was 5 when this happened, he had a lot of cats. I cried for days when I realized they were all gone.

Heck, I was coaching my brother’s little league team back then, and we had ash fallout, like light snow, in California. Went on for a week. There were bad air health advisories on the news.

I even remember some guy was video taping the event, and got killed from the blast. Trees were tumbled like lincoln logs. Brutal disaster.

Next time will be worse.