When Mount Agung in Indonesia erupted in 2017, the search was on to find out why it had stirred. Thanks to information on ground deformation from the Copernicus Sentinel-1 mission, scientists now have more insight into the volcano’s hidden secrets that caused it to reawaken.

After lying dormant for more than 50 years, Mount Agung on the Indonesian holiday island of Bali rumbled back to life in November 2017, with smoke and ash causing airport closures and stranding thousands of visitors.

Fortunately, it was preceded by a wave of small earthquakes, signalling the imminent eruption and giving the authorities time to evacuate around 100 000 people to safety.

The prior event in 1963, however, claimed almost 2000 lives and was one of the deadliest volcanic eruptions of the 20th century. Knowing Agung’s potential for devastation, scientists have gone to great lengths to understand this volcano’s reawakening.

And, Agung has remained active, slowly erupting on and off since 2017.

Agung and Batur volcanoes

Bali is home to two active stratovolcanoes, Agung and Batur, but relatively little is known of their underlying magma plumbing systems. A clue came from the fact that Agung’s 1963 eruption was followed by a small eruption at its neighbouring volcano, Batur, 16 km away.

A paper published recently in Nature Communications describes how a team of scientists, led by the University of Bristol in the UK, used radar data from the Copernicus Sentinel-1 mission to monitor the ground deformation around Agung.

Their findings may have important implications for forecasting future eruptions in the area, and indeed further afield.

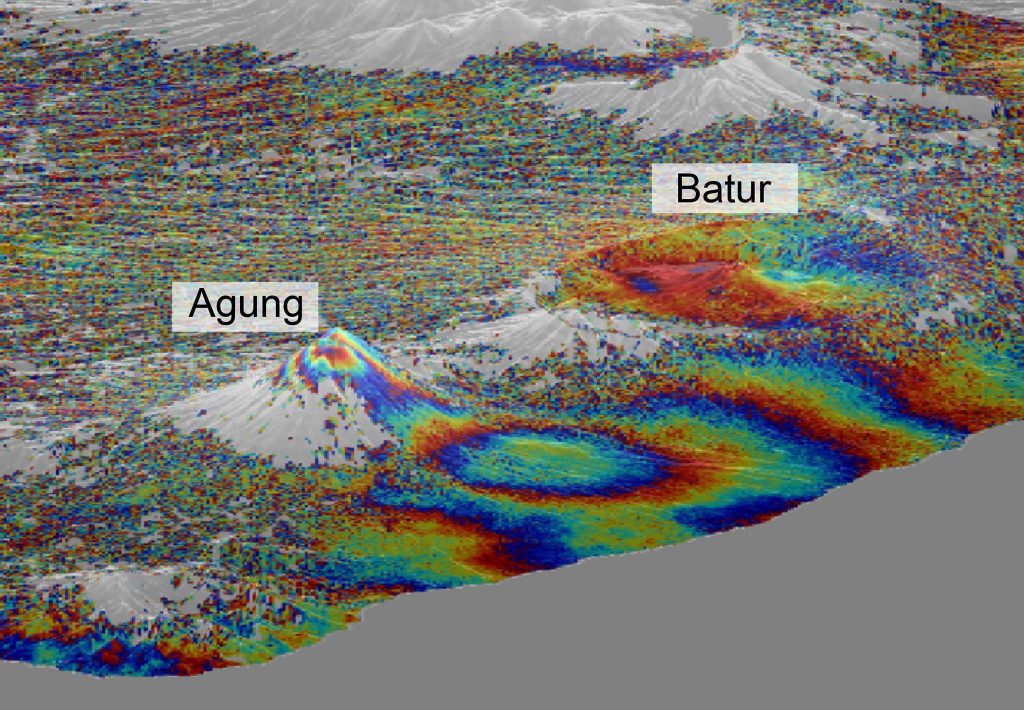

They used the remote sensing technique of interferometric synthetic aperture radar, or InSAR, where two or more radar images over the same area are combined to detect slight surface changes.

Tiny changes on the ground cause differences in the radar signal and lead to rainbow-coloured interference patterns in the combined image, known as a SAR interferogram. These interferograms can show how land is uplifting or subsiding.

Juliet Biggs from Bristol University’s School of Earth Sciences, said, “Using radar data from the Copernicus Sentinel-1 radar mission and the technique of InSAR, we are able to map any ground motion, which may indicate that fresh magma is moving beneath the volcano.”

In study, which was carried out in collaboration with the Center for Volcanology and Geological Hazard Mitigation in Indonesia, the team detected uplift of about 8–10 cm on Agung’s northern flank during the period of intense earthquake activity prior to the eruption.

Fabien Albino, also from Bristol’s School of Earth Sciences and who led the research, added, “Surprisingly, we noticed that both the earthquake activity and the ground deformation signal were five kilometres away from the summit, which means that magma must be moving sideways as well as vertically upwards.

“Our study provides the first geophysical evidence that Agung and Batur volcanoes may have a connected plumbing system.

“This has important implications for eruption forecasting and could explain the occurrence of simultaneous eruptions such as in 1963.”