Supervolcanoes have the power to trigger widespread climate change and global starvation.

Here a few steps you can take to prepare.

Although they might occur infrequently, even on a geological timeline, supervolcanoes are by no means insignificant. Unlike isolated incidents of tragedy that affect different people groups around the world, one supervolcano could pose a threat to all life on Earth.

In his book End Times: A Brief Guide to the End of the World, bestselling author Bryan Walsh examines a variety of existential risks – global threats so great they could trigger human extinction, or reduce the human population so drastically that there’d be no recognizable future.

In addition to cataclysmic asteroid disasters and superintelligent AI robots, Walsh’s book considers the very real threat which supervolcanoes impose on the human race.

He also uncovers what we can do to be better prepared to survive the aftermath of a supervolcano eruption.

The looming threat of supervolcanoes

“The true horror of an existential threat is not my death, it’s not your death, or the death of all 7.7 billion people that exist now,” says Walsh, “it’s the nullification of the future.“

Although it might not occur in the next five, hundred, or few thousand years, Walsh says the human race should still be preparing for the next global volcanic event.

But as you already know we are not ready for the next Big One.

Supervolcanoes have already threatened the future of humanity multiple times. Seventy-five thousand years ago, the Toba volcano erupted on what is today, the island of Sumatra, Indonesia.

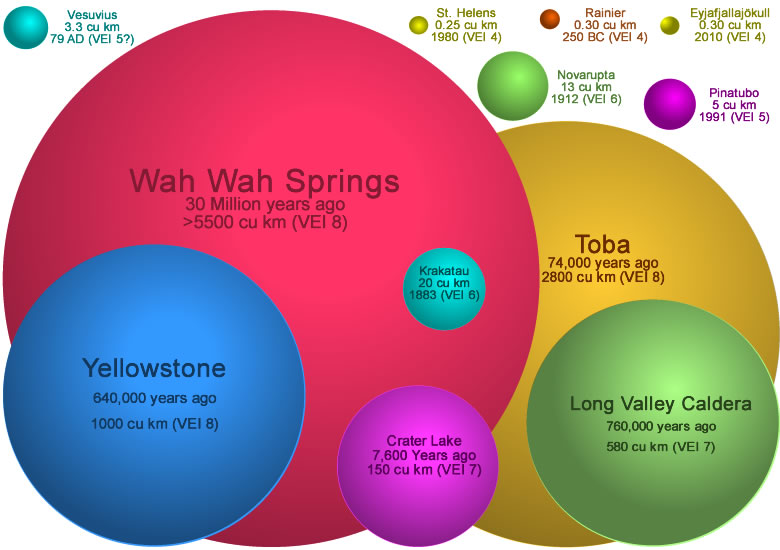

The Mount Toba Eruption ejected an estimated 2,800 cubic kilometers of volcanic material (more than 1.5 times the volume of Lake Ontario) into the atmosphere.

Researchers believe that the aftermath of the eruption of Mount Toba pushed humanity to the brink of extinction, creating an evolutionary bottleneck that some of our ancestors thankfully managed to survive.

The magnitude and aftermath of a supervolcano

Like the Richter Scale used to measure earthquakes and the Saffir-Simpson Wind Scale that rates hurricanes, volcanoes are measured using their own unique scale, called the Volcanic Explosivity Index (VEI).

The VEI ranks volcanoes on a scale of magnitude, ranging from one (minor eruptions) to eight (biggest volcano eruptions) based on the volume of erupted materials. With each number, the volume of ejected materials increases by a factor of 10, and only volcanoes of “VEI 8” magnitude are considered supervolcanoes.

Although a VEI 8 and VEI 5 are only three points away from each other on the scale, they depict quite different events. For example, the VEI 5 eruption of Mount St. Helen’s in May of 1980 didn’t even spew one-percent of the volume ejected by the VEI 8 Mount Toba eruption.

A supervolcano would release enough pumice, ash, and rock into the atmosphere to have a disastrous effect on the climate.

The largest volcano eruption of the last 10,000 years (and of our recorded history) is the 1815 eruption of Mount Tambora in Indonesia. Ten-thousand inhabitants of the island perished instantly and others nearby fell victim to the immediate effects of the eruption, such as falling debris, landslides, and tsunamis.

Tambora also had serious global consequences. The VEI 7 eruption ejected about 150 cubic kilometers of volcanic materials into the atmosphere, triggering a widespread climate change which reached as far as Europe and North America.

The year 1816 became known as “the year without a summer.” As late-season frosts decimated crops, countless people succumbed to starvation as a result of the eruption.

Imagine aftereffects like those of Tambora’s 1815 eruption that circle the globe and last for years. Cold, dark, and hungry – that’s what the aftermath of a supervolcano would look like.

Walsh says we should start developing methods of food production that don’t require sunlight, and improve systems that monitor geological activity.

When a volcano erupts, it releases pumice, ash, rock, and aerosols (primarily sulfur) which enter the atmosphere and prevent sunlight from reaching the Earth’s surface.

In the case of Tambora, surface temperatures dropped an average of 3 ℃ (5.4 ℉) for about a year. Experts estimate that, following the Mount Toba supervolcano eruption, global surface temperatures might have dropped as much as 15 ℃ (59 ℉) for a period of roughly 1,000 years.

In addition to the famine which would ensue following the eruption of a supervolcano, Walsh takes care to point out that the ash itself is dangerous.

On a microscopic level, pyroclastic materials contain glass and sharp, hook-shaped rocks which destroy the tissues of the human body, making it unsafe to go outside or even breathe. Volcanic ash is also heavy, like cement, and will destroy buildings, caving in rooftops.

How can we survive a supervolcano?

Neither Walsh, nor End Times is all doom and gloom. The book does offer steps that the human race can take to prepare for a cataclysmic event the size of a supervolcano.

To start, Walsh says it’s essential that people comprehend and accept the reality of these threats. Although they occur infrequently, people should not continue to think of them as events that could occur only in bygone eons.

“If we go extinct now, almost certainly, it’s because we did not try hard enough to keep ourselves safe.”

After people gain awareness, Walsh says we should start developing methods of food production that do not depend on sunlight. We can also work on improving our global systems for monitoring geological activity.

We understand what causes a volcano to erupt and can recognize some of the signs of an impending eruption. But with improved monitoring systems, we’ll be able to make preparations, like moving food into storage, as soon as we detect early signs of a major volcanic event.

It’s been 27,000 years since the last supervolcano eruption. “If we go extinct now,” says Walsh, “almost certainly, it’s because we did not try hard enough to keep ourselves safe.“

Freethink / Guardians of the Apocalypse kindly asked to publish this article on Strange Sounds. More supervolcanic news on Strange Sounds and Steve Quayle.

M 5.2 – 151km W of Port Hardy, Canada

2020-05-23 02:14:51 (UTC)50.428°N 129.509°W10.0 km depth

red alert for Cascadia will go off sooner than later. FEMA is already in WA state ?

Strange sounds writes best articles in the world. I defend strange sounds till death. OYVEY you get your s first? lol.

6.1 quake near end of Baja California.

Earth is at max 20k years old. This is all bs (((science)))

Take the redpill before posting shit