Killer lakes contain high concentration of gas inside that may erupt suddenly!

Knowing the high concentration of methane and CO2 in the Louisiana Sinkhole, could it suddenly explode?

The Setting

A tragic phenomenon occurred in Cameroon in the mid 1980s, where lakes seemed to be killing people.

The first event happened in 1984, when 37 people near Lake Monoun died suddenly. The second event, however, was much more deadly.

In August 1986, Lake Nyos released a cloud of carbon dioxide (CO2) which hugged the ground and flowed down surrounding valleys to suffocate thousands of local villagers and animals. Overall, more than 1,700 people were killed as far as 26 km away from the lake.

A third lake, Lake Kivu, on the Congo-Rwanda border in Central Africa, is also known to act as a reservoir of carbon dioxide and methane. These three lakes contain very high concentrations of CO2 in their depths and can be lethal to thousands of people that live around them. If Lake Kivu were to explode, over two million people who live around it would be in danger. – USGS

It has been recently reported that the Louisiana sinkhole contains large concentration of CO2 and methane which could explode. Moreover, officials ask residents to leave their houses and yet the workers have to move. Although the geological conditions are totally different, it may turn out that the too high methane and carbonic acid concentrations measured in the sinkhole water (reports of bubbling at the surface) may be once released in the air (like in Africa), thus becoming the next exploding lake.

The scientific explanation

The science behind the buildup of CO2 is fairly simple. These deep lakes occur near a dormant volcano. The real danger is generated by subsurface magma about 50 miles below the lakes. The magma releases the CO2 and other gases, which travel upward through the Earth. The CO2, instead of being released harmlessly into the atmosphere, collects in the cold water at the bottom of the lake. The amount of gas that can be dissolved in the water is dependent on water temperature and pressure. The greater the pressure and colder the water, the more gas can be trapped.

None of this would be particularly hazardous if the water at the bottom of the lake were to regularly rise to the surface, where the gas could be safely released.

The problem is that the waters of these lakes, like many tropical lakes, are usually quite still with little annual mixing of the water layers. Over time, the lowest levels of the lakes become super-saturated with CO2. This gas can quickly escape when the lake is disturbed by a landslide, earthquake, violent storm, or other disturbance.

The sudden release of CO2 can be fatal. CO2 is heavier than air and when it was released in previous explosions it poured over the rim of the crater and down into the surrounding low-lying valleys. Although CO2 normally makes up 0.03% of the atmosphere, concentrations of more than 10% can be fatal. The unfortunate villagers around Lake Nyos literally suffocated under the heavy poisonous cloud of CO2 gas. – USGS

Solutions to the problem

Since then, engineers have been artificially removing the gas from the lake through piping. This photo shows the Lake Nyos pipe in operation. The 200-meter-long pipe is suspended from the raft and allows gas-rich water from the lake bottom to vent to the surface, where the CO2 dissipates into the atmosphere at a controlled rate. The shed on the control raft is about 6 feet high and the fountain is about 120 feet high. There are no pumps involved because the CO2 drives the fountain, just like a shaken bottle of champagne.

In the USA

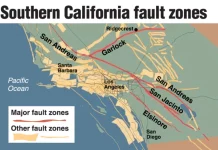

While exploding lakes in Cameroon are unique, volcanic CO2 poses problems in some areas of the U.S., as well. In fact, in 1994, USGS researchers discovered that large volumes of CO2 were seeping from beneath Mammoth Mountain, a young volcano in the Long Valley area of California. The seepage was triggered by a persistent swarm of earthquakes, and killed more than 100 acres of trees. The CO2 also forced the U.S. Forest Service to close the area to camping. The USGS continues to monitor this area, where earthquakes and gas seepage remain a concern.

Hopefully, the Louisiana sinkhole will not explode! At least not now!

[…] Have you heard about exploding killer lakes? […]

[…] Have you heard about exploding killer lakes? […]

[…] Anyway, we must research this phenomenon urgently, to prevent a possible collapse or implosion of the Yamal Peninsula. […]

[…] Learn more about killer lakes! […]

[…] level. However, it does not come up suddenly enough or in large enough amounts to cause explosions (except for these). Also, burning methane makes flames, and a couple of the articles that Google listed point out […]

[…] I wasn’t totally wrong when trying to link the Louisiana sinkhole to exploding lakes! […]

[…] Learn more about killer lakes here. […]

[…] Did you know that the Louisiana sinkhole may also explode once? […]

[…] of Mexico! In a previous article, I only propose that the Louisiana sinkhole could once erupt like killer lakes in Africa. Here, he goes further and the analysis is pretty […]

[…] this video brings up old articles, they are in accordance with my previous thoughts that the Louisiana sinkhole could explode if the gas (methane and CO2) are not rapidly moved out. […]

[…] The Killer Lake Phenomena: Is the Louisiana Sinkhole Becoming the Next “Exploding Lake”? […]

[…] The Killer Lake Phenomena: Is the Louisiana Sinkhole Becoming the Next “Exploding Lake”? […]

Thank you!