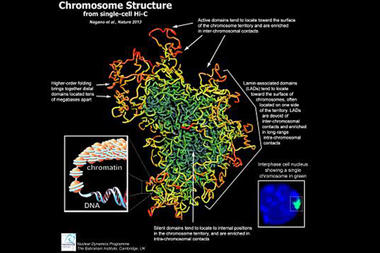

Last week, a paper published in Nature presented the first 3D model of the X chromosome. And believe it or not: it’s not X-shaped but is more similar to a plate of sticky spaghettis.

But why are X chromosome always X-shaped?

That the X chromosome is not shaped like an “X” upends popular renderings of the chromosome, but it is not a revelation to scientists. The tale of how the X chromosome came to be pictured as an “X” is a long one, unfolding around 1890 when scientists were first piecing through the foreign language of our bodies and happened on an unusual chromosome. It was called “X,” a placeholder for “unknown.” Later, its brother chromosome was called “Y,” after the next letter in the alphabet.

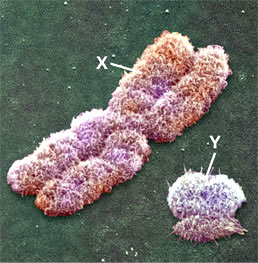

Then, it turned out that chromosomes – all of them – are shaped like an “X,” but for just a moment. This X-shaped structure is a pit stop right before an organism’s cells divide, in what is known as mitosis. The X-shape is also not one chromosome: it’s two. One of the two angled columns that make that “X” is a new, identical copy of the other, made so that when the cell splits, one chromosome goes to one cell, and the other goes to the other cell.

The mitosis shape has been the preferred means of representing chromosomes, since this is the point at which each chromosome (or, really, pair of chromosomes) is distinguishable from another pair, and, no less, has been neatly packaged into a familiar shape.

[…] to, apparently popular, belief, the X Chromosome is not X […]