Not far from Santa Catalina Island, in an ocean shared by divers and fishermen, kelp forests and whales, David Valentine decoded unusual signals underwater that gave him chills.

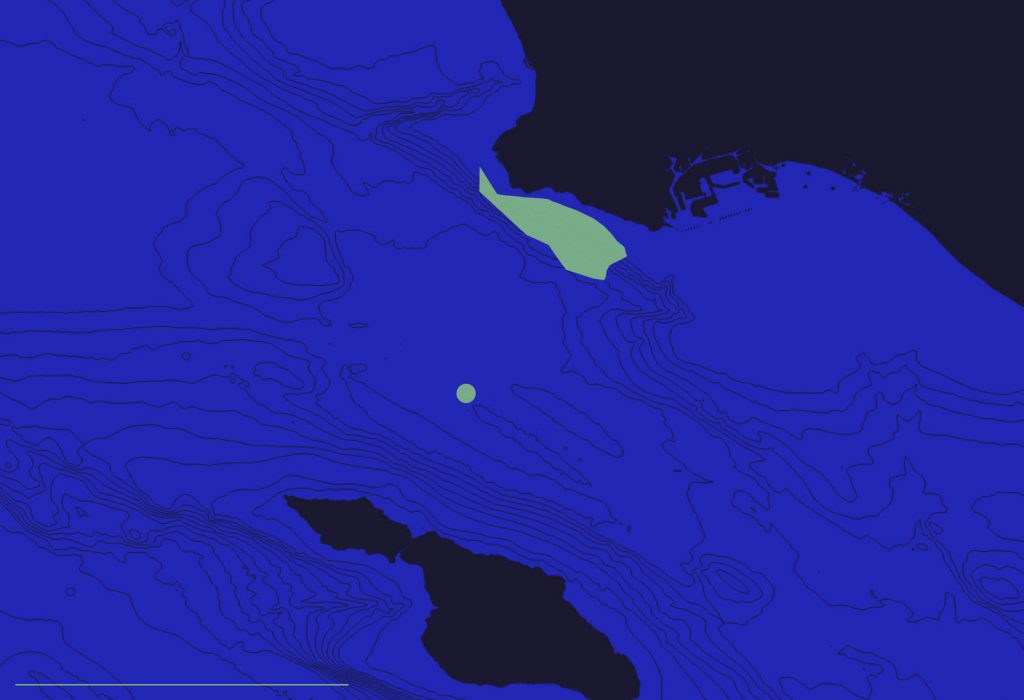

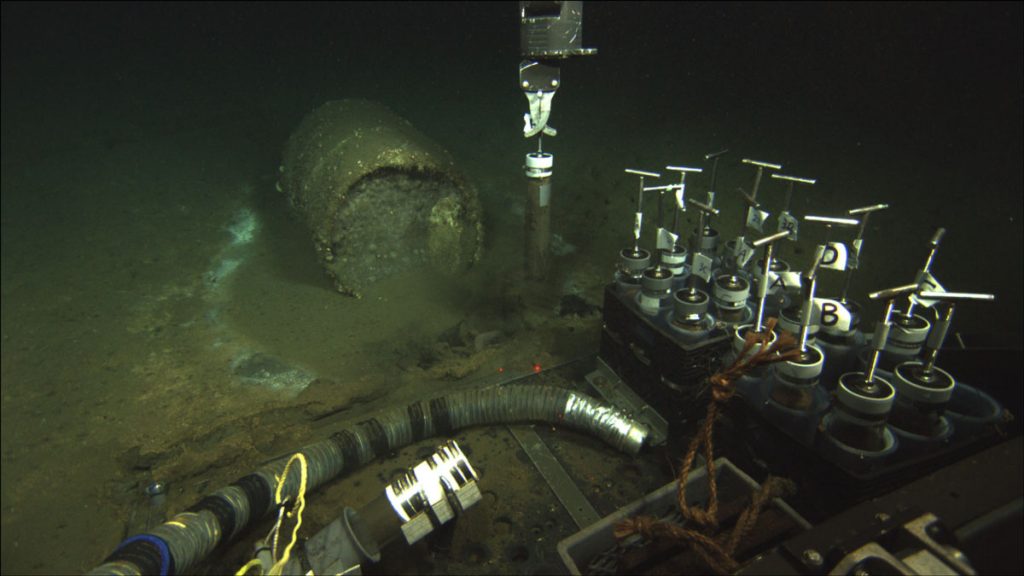

The UC Santa Barbara scientist was supposed to be studying methane seeps that day, but with a deep-sea robot on loan and a few hours to spare, now was the chance to confirm an environmental abuse that others in the past could not. He was chasing a hunch, and sure enough, initial sonar scans pinged back a pattern of dots that popped up on the map like a trail of breadcrumbs.

The robot made its way 3,000 feet down to the bottom, beaming bright lights and a camera as it slowly skimmed the seafloor. At this depth and darkness, the uncharted topography felt as eerie as driving through a vast desert at night.

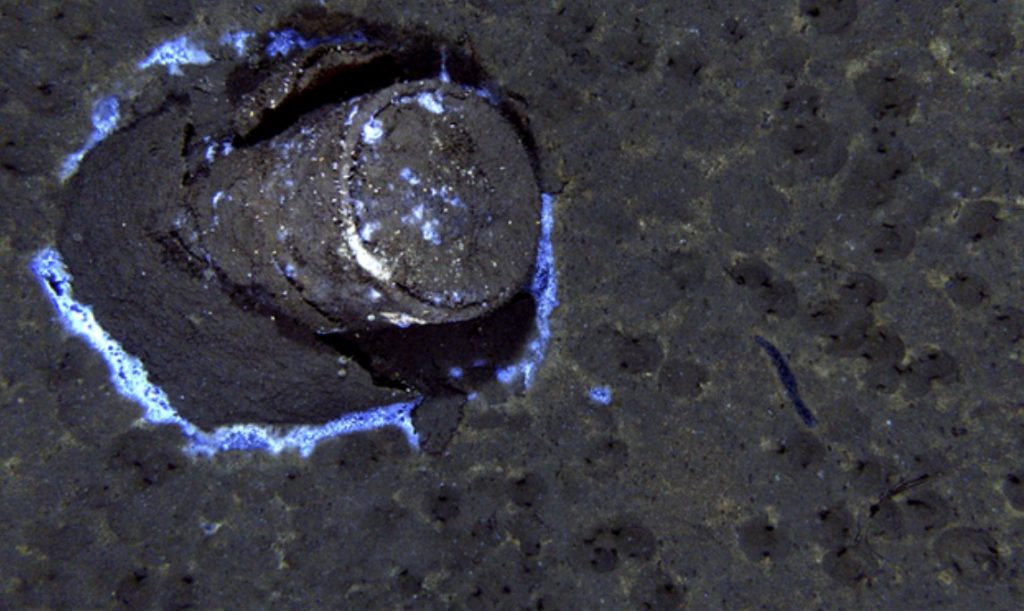

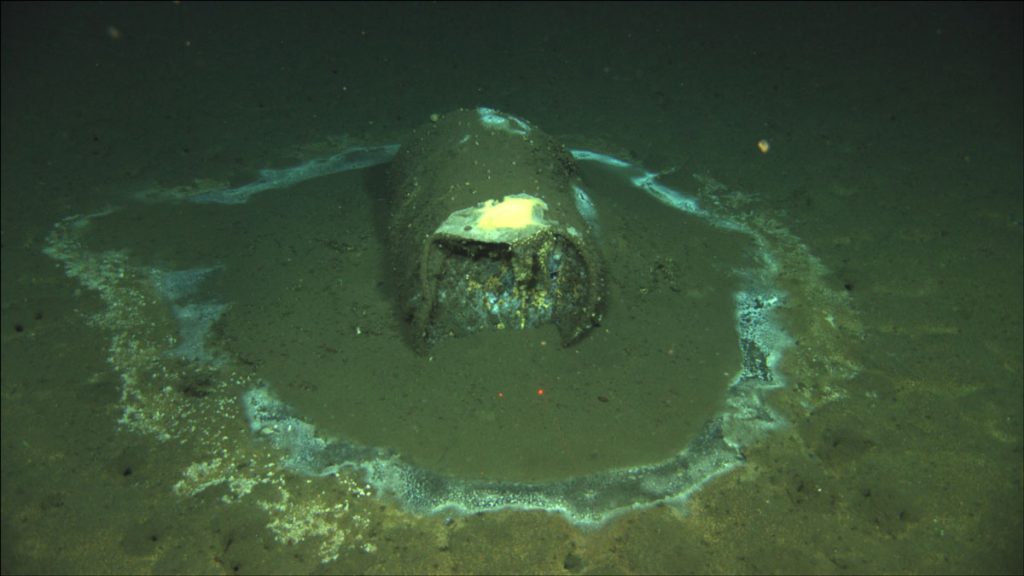

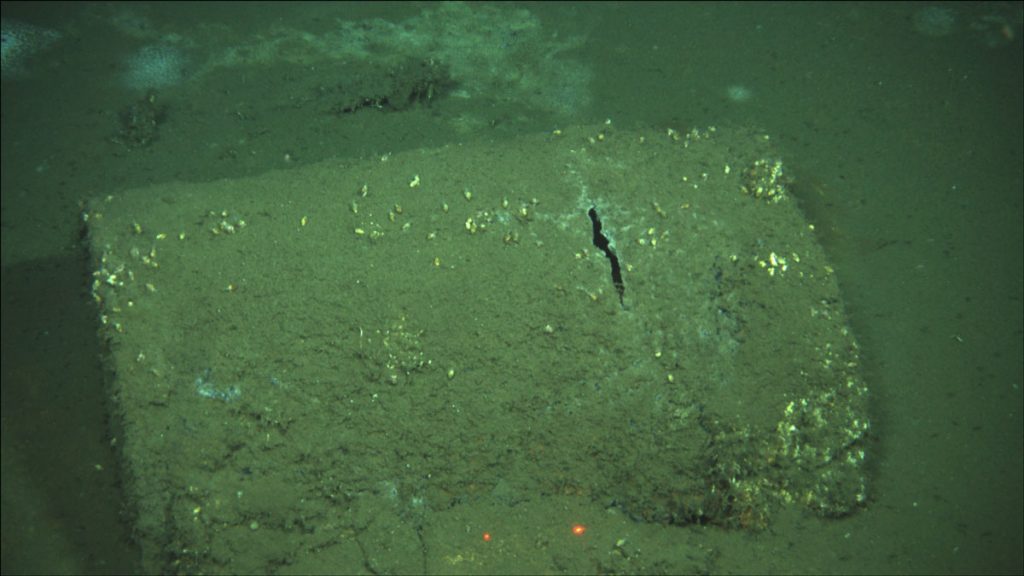

And that’s when the barrels came into view.

Barrels filled with toxic chemicals banned decades ago.

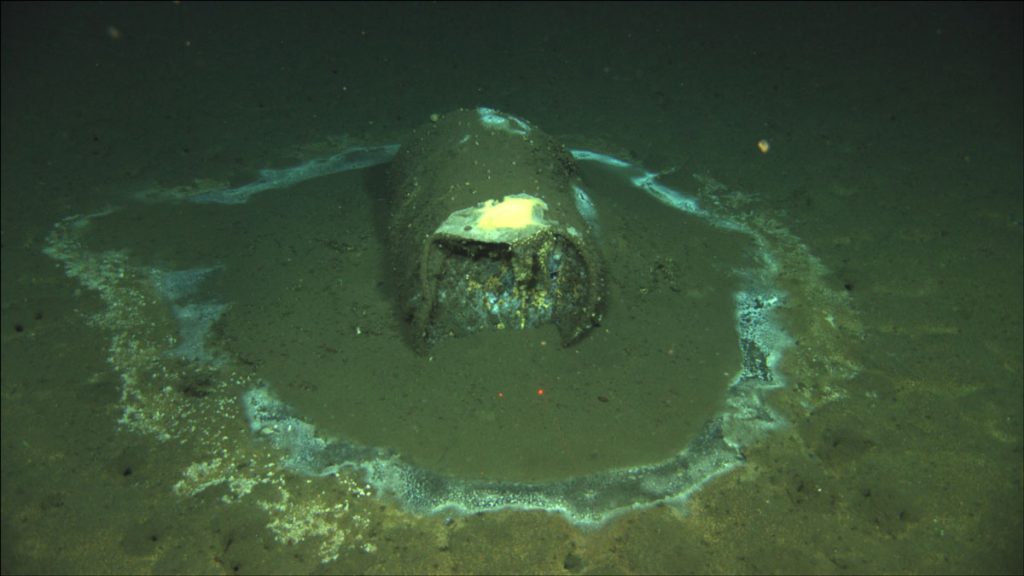

Leaking.

And littered across the ocean floor.

“Holy crap. This is real,” Valentine said. “This stuff really is down there.

“It has been sitting here this whole time, right off our shore.”

Tales of this buried secret bubbling under the sea had haunted Valentine for years: a largely unknown chapter in the most infamous case of environmental destruction off the coast of Los Angeles — one lasting decades, costing tens of millions of dollars, frustrating generations of scientists. The fouling of the ocean was so reckless, some said, it seemed unimaginable.

As many as half a million of these barrels could still be underwater right now, according to interviews and a Times review of historical records, manifests and undigitized research. From 1947 to 1982, the nation’s largest manufacturer of DDT — a pesticide so powerful that it poisoned birds and fish — was based in Los Angeles.

An epic Superfund battle later exposed the company’s disposal of toxic waste through sewage pipes that poured into the ocean — but all the DDT that was barged out to sea drew comparatively little attention.

Shipping logs show that every month in the years after World War II, thousands of barrels of acid sludge laced with this synthetic chemical were boated out to a site near Catalina and dumped into the deep ocean — so vast that, according to common wisdom at the time, it would dilute even the most dangerous poisons.

Regulators reported in the 1980s that the men in charge of getting rid of the DDT waste sometimes took shortcuts and just dumped it closer to shore.

And when the barrels were too buoyant to sink on their own, one report said, the crews simply punctured them.

The ocean buried the evidence for generations, but modern technology can take scientists to new depths. In 2011 and 2013, Valentine and his research team were able to identify about 60 barrels and collect a few samples during brief forays at the end of other research missions.

One sediment sample showed DDT concentrations 40 times greater than the highest contamination recorded at the Superfund site — a federally designated area of hazardous waste that officials had contained to shallower waters near Palos Verdes.

The world today wrestles with microplastics, bisphenol A (BPA), per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) and other toxics so unnatural they don’t seem to ever go away.

But DDT — the all-but-indestructible compound dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane, which first stunned and jolted the public into environmental action — persists as an unsolved and largely forgotten problem.

Signs warning of tainted fish to this day still cover local piers. Recent studies show our immune systems may be compromised. A new generation of women — exposed to DDT from their mothers, who were exposed by their mothers — grapples with the still-mysterious risks of breast cancer.

The contamination in sea lions and dolphins continues to stump scientists, and the near extinction of falcons and bald eagles shows how poisoning one corner of the world can ripple across the whole ecosystem.

Decades of bureaucracy and competing environmental issues have diverted the public’s attention. Valentine hoped digging up physical evidence from the seafloor would get more people to care, but calls and emails to numerous officials since his discovery have gone nowhere.

Rallying for the deep ocean is not easy, Valentine acknowledged, even though we rely on the health of these waters far more than we know: “The fact that there could be half a million barrels down there … we owe it to ourselves to figure out what happened, what’s actually down there and how much it’s all spreading.”

Once hailed as a major scientific achievement, DDT combated both malaria and typhus during World War II. It was so potent that a single application could protect a soldier for months. The U.S. Army’s chief of preventive medicine, Brig. Gen. James Simmons, famously praised the chemical as “the war’s greatest contribution to the future health of the world.”

DDT was also considered a wonder pesticide, combatting malaria and preventing crop failures across the world.

Manufacturers rushed to supply the postwar demand — including Montrose Chemical Corp. of California, which opened its plant near Torrance in 1947. The chemical industry was celebrated at the time for boosting the nation into greater prosperity and preventing crop failures across the globe. The United States used as much as 80 million pounds of DDT in one year.

But there were two edges to this sword

A top U.S. Department of Agriculture scientist had urged the military not to allow DDT insecticides for commercial use without further research, worried about “the effect they may have on soils and on the whole balance of nature.”

Even Swiss chemist Paul Hermann Müller, who won a Nobel Prize in 1948 for discovering DDT as a pesticide, cautioned that he himself did not fully understand how the chemical interacted with the living world. Decades of painstaking study still lay ahead for biologists, he said.

Rachel Carson, a marine biologist, heeded these words in 1962 and ignited a movement against what she called “the reckless and irresponsible poisoning of the world that man shares with all other creatures.”

Her revolutionary book “Silent Spring” evoked the sudden silence of songbirds missing in the skies — alerting unknowing people to the dangers of long-term exposure, even in tiny doses, to a chemical that they could not physically avoid.

DDT is so stable it can take generations to break down. It doesn’t really dissolve in water but stores easily in fat. Compounding these problems is what scientists today call “biomagnification”: the toxin accumulating in the tissues of animals in greater and greater concentrations as it moves up the food chain.

food web problem

Consider phytoplankton, the microscopic algae that are the base for almost all food webs in the ocean.

DDT-contaminated phytoplankton get eaten by zooplankton, which fish and whales consume by the thousands.

In 1969, shipments of jack mackerel from Southern California were recalled because DDT levels were as high as 10 parts per million, or ppm — double what the U.S. Food and Drug Administration considered safe for consumption at that time.

Tumors started appearing on bottom-feeding fish like white croaker.

In that same year, California brown pelicans, which eat the fish, laid eggs on Anacapa Island with chemicals broken down from DDT averaging 1,200 ppm.

Scientists discovered that the chemicals led to eggshells so thin that the chicks would die. Bald eagles had also vanished from the Channel Islands, along with peregrine falcons and the brown pelicans.

Similarly, sea lions with more than 1,000 ppm in their blubber were giving birth to pups prematurely. Bottlenose dolphins had concentrations as high as 2,000 ppm.

Montrose executives aggressively defended DDT through the 1960s as the public reckoned with these alarming new concerns about food chains and poisoned ecosystems.

They said in letters and editorials that DDT played a vital role in society when properly used and was not a serious threat to human health. They accused environmentalists of scare tactics and misleading information and touted the company’s reputation of making the best DDT in the world — a technical grade sold to other firms that would then dilute it into specific insecticides.

The company was supplying governments from Brazil to India, they said, and even the World Health Organization. International malaria eradication programs turned to Montrose for supplies.

But after years of intense inquiries, government officials said they were convinced that the chemical posed unacceptable risks to the environment and potential harm to human health. In 1972, the U.S. finally banned the use of DDT.

Demand was still strong in other countries, however, so the chemical plant in Los Angeles kept churning out more. Montrose managed to operate for another 10 years before the factory, looming over Normandie Avenue near Del Amo Boulevard, finally went dark.

Dumping of barrels in LA

In the early 1980s, a young scientist at the California Regional Water Quality Control Board in Los Angeles heard whispers that Montrose once dumped barrels of toxic waste directly into the ocean. People at the time were hyper-focused on the contamination problems posed by poorly treated sewage, but Allan Chartrand was curious about the deep-sea dumping and started poking around.

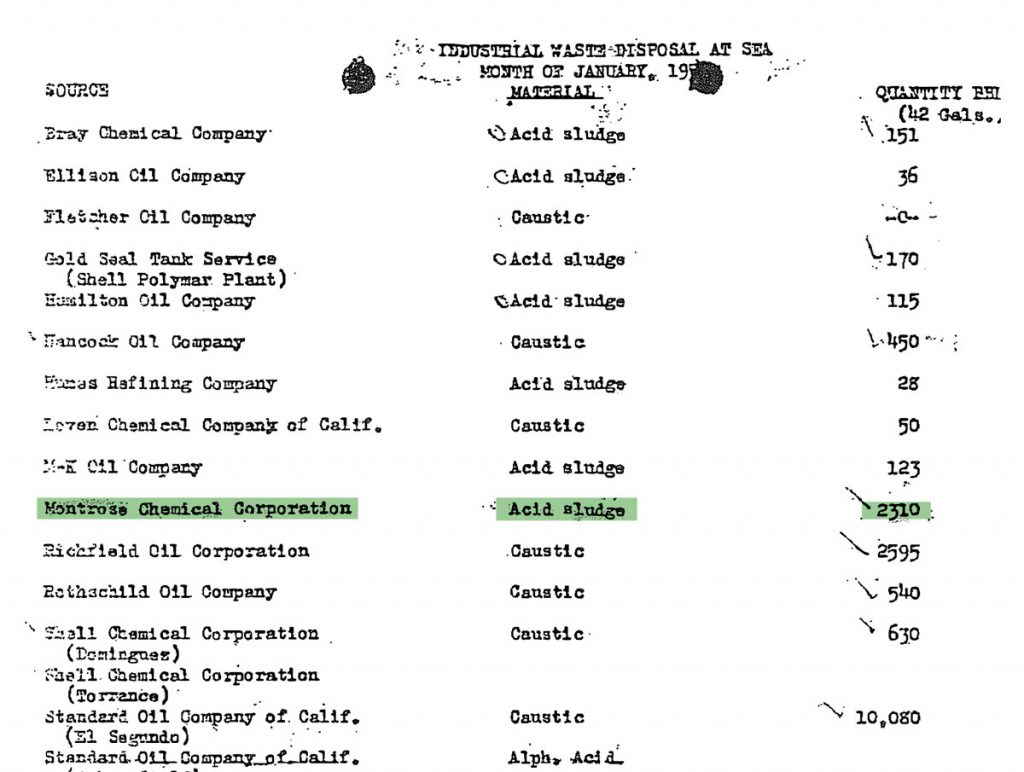

He called Montrose, and to his surprise, the staff pulled out all their files. He and a team of regulatory scientists combed through volumes of shipping logs, which showed that more than 2,000 barrels of DDT-laced sludge were dumped each month.

They did the math: Between 1947 and 1961, as much as 767 tons of DDT could have gone into the ocean.

“We found actual photos of the workers at 2 in the morning dumping — not only dumping barrels off of the barges in the middle of the Santa Monica Basin,” he said, “but before they would dump the barrels, they would take a big ax or hatchet to them, and cut them open on purpose so they would sink.”

Dumping industrial chemicals near Catalina was an accepted practice for decades

On a recent morning, Chartrand rummaged through stacks of yellowing papers and reports detailing everything he had discovered so many decades ago. Now a seasoned eco-toxicologist in Seattle, he never understood why all this information wound up gathering dust — undigitized and largely forgotten.

He pulled out faded reports that his team had published from 1985 to 1989, summarizing what they had found at Montrose and in the water quality control board’s own records. “This makes my heart sing,” he said, as he reread conclusions that still resonate today.

Chartrand said he was astonished to learn this kind of activity was allowed. Federal ocean dumping laws dated back to 1886, but the rules were focused on clearing the way for ship navigation. It wasn’t until the Marine Protection, Research and Sanctuaries Act of 1972, also known as the Ocean Dumping Act, that environmental impacts were considered.

Landfills could hold only so much, and people were concerned about burning toxics into the air — but the Pacific Ocean seemed a good alternative. Explosives, oil refinery waste, trash and rotting meats all went into the ocean, along with beryllium, various acid sludges, even cyanide.

Dilution is the solution to pollution, the saying used to go, but at what cost? The ocean covers more than 70% of the planet, but it can absorb only so much. What we eat, what we breathe is ultimately dictated by what we do to the sea.

“It’s just sad, sad, sad,” Chartrand said. “When stuff’s being dumped offshore like that, it’s in the dead of night, nobody’s seeing it. It’s out of sight, out of mind.”

For years, a company called California Salvage docked at the Port of Los Angeles, loaded up Montrose’s DDT waste and hauled everything out to sea. Workers were instructed to dump in a designated spot, dubbed Dumpsite No. 1, that was about 10 nautical miles northwest of Catalina.

But compliance inspections were infrequent, and crews sometimes took shortcuts. Chartrand discovered notes from California Salvage indicating they had decided to dump elsewhere because Dumpsite No. 1 was in line of a naval weapons firing range.

The report concluded that these companies likely dumped in closer, much shallower waters.

“Our report caught them red-handed,” Chartrand said. “Here I was this young guy — newly married, just had my first kid, got my new job at the water quality control board — heard about this dumping, went down to Montrose … and it very quickly got so much bigger than me.”

Court battle

In 1990, a few years after Chartrand compiled his reports, the Environmental Protection Agency teamed up with the state and launched a court battle against Montrose and a number of other companies under the Superfund law. Environmental groups expected the lawsuit — the largest in U.S. history alleging natural resource damages from chemical dumping — to be a landmark case in resolving coastal pollution issues.

Chartrand and dozens of others were pulled in to testify. Science was disputed in court, evidence debated, expertise challenged. In numerous depositions, former factory workers were grilled on how they operated.

Bernard Bratter, a Montrose plant superintendent, described how they would call California Salvage to dump its acid waste in bulk: “The trucks would come in, we’d load the trucks, they would then haul them down to the harbor where they had their barges, and the truck would unload into the barge, and when there was enough liquid in the barge, they’d haul the barge out to the specified area in the ocean and release the acid.”

Montrose officials, who had filed counterclaims, asked the court to exclude the evidence presented on ocean dumping — arguing that such dumping wasn’t relevant.

They said the government’s natural resources damage claim was based solely on the release of DDT through the sewer system to the Palos Verdes shelf, and that attorneys could not prove that Montrose’s disposal of DDT-contaminated waste into the deep ocean actually hurt various bird species.

They also questioned Chartrand’s calculations of how much DDT went into the ocean and made the point that there was nothing secret or illegal about the dumping at the time. The government, they said, allowed this to happen.

In an interoffice correspondence in 1985, Samuel Rotrosen, Montrose’s president at the time, wrote that “it is true that from 1947, when the plant started up, until sometime in the 1950s we disposed of our waste sulfuric acid at sea through California Salvage Company who barged it out to state-approved dumping areas.

“We stopped this disposal after we installed our acid-recovery plant, at which time we sold the acid to fertilizer makers,” he said. “Because our acid contained traces of DDT (50-250 ppm) … the fertilizer producers would no longer take it, and so we disposed of it at landfills.”

Science wins

As the court battle waged on, a handful of curious scientists kept trying to solve the DDT questions at the bottom of the ocean.

Chartrand did not have a deep-sea robot, but he figured out a way to collect sediment samples and clumps of tar by dragging a large otter trawl net along the seafloor. He also took samples of rattails, kelp bass and other fish from different depths of the ocean.

He called Robert Risebrough, a legend among DDT scientists whose testimonies in the 1960s and early 1970s helped Congress understand why the chemical should be banned. Risebrough, a UC Santa Cruz research ecologist at the time, ran the samples and authored a sweeping study. He confirmed the existence of considerable concentrations of DDT chemicals in both the sediments and the “tar cakes” by the dumpsites.

It was unclear how much the DDT could move through the water at such depths, where there is little oxygen, he said, but the dumping was close enough to the Channel Islands that the upwelling of deeper water common in this area could stir up what enters the food chain.

And if the barrels were indeed punctured, he added, some of the sludge could have leaked out on its way down to the seafloor.

He had a strong suspicion that the disappearance of bald eagles from Catalina was connected to the dumping operations, but he didn’t have the data to confirm it. DDT contamination was also significantly higher in birds that fed on fish, compared with birds that ate mostly rodents and prey on land — another clue that the DDT from the ocean dumping was harming wildlife.

He called for more studies to connect the dots, but Chartrand had run out of funding. Chartrand held on to what he could — even the remaining samples that neither he nor Risebrough could bear to throw away. Some of that deep sea sediment has yet to be tested.

“They’re in a deep freeze now, but because it’s DDT, even though it’s been 30, 40 years, they’re still valid,” Chartrand said. “If we could get the funding, those are still worth running.”

M. Indira Venkatesan, a geochemist at UCLA who studied how chemicals moved through the sea, had taken one of these samples in the early 1990s and run her own analyses. She, too, concluded there must be a DDT source in the ocean much larger than just what had come out of the sewage closer to shore.

She collected additional sediment cores from the seafloor by a manual pulley that her technicians and graduate students spent hours pulling up. Her team distinguished the DDT “fingerprint” for Montrose’s ocean-dumped waste and discussed the upward and downward diffusion of DDT in the sediments.

“It gets resuspended and remobilized. That’s why you see it all over the basin,” she said. “I knew, I just knew, this DDT source was significant, just from the chemical analysis, but we couldn’t show the extent of the dumping, nor the number of barrels.”

Back in court, the arguments were focusing on the more tangible: the hundreds of tons of DDT and PCBs, another toxic chemical, that had been released two miles off the coast of Palos Verdes where the sewage emptied into the ocean. Many saw the need to make this public health problem — much closer to shore, with visible harm to humans and the ecosystem — a top priority.

The site — spread across more than 17 square miles — was declared a Superfund cleanup in 1996. About 200 feet deep, it was considered one of the most complicated hazard sites in the United States — at least three times deeper than similar Superfund sites in Boston and New York harbors.

By late 2000, the parties decided to settle. They negotiated a consent decree midway through trial — no sides admitting fault, with an agreement that more than $140 million would be paid by Montrose, several other companies that owned or operated a share of the plant, and local governments led by the Los Angeles County Sanitation Districts.

The settlement — one of the largest in the nation for an environmental damage claim — would pay for cleanup, habitat restoration and education programs for people at risk of eating contaminated fish.

“This Decree was negotiated … in good faith at arm’s length to avoid the continuation of expensive and protracted litigation and is a fair and equitable settlement of claims which were vigorously contested,” according to the decree, which mentioned that the damage claim includes “any ocean dumpsites used for disposing of wastes from the Montrose Plant Property.”

Nobody in their worst nightmares, ever thought there would be half a million barrels of DDT waste dumped into the ocean off of L.A. County’s coast.

Yes, and this stuff is spreading. These barrels do seem to be leaking over time. This toxic waste is just kind of bubbling down there, seeping, oozing, I don’t know what word I want to use. … It’s not a contained environment.

These chemicals are still out there, and we haven’t figured out what to do. They are an issue, and we still don’t have a plan.

Disposing any waste, where you don’t see and forget about it, does not solve the problem. The problem eventually comes back to haunt us.

Yes, it’s like the Runit dome… the next radioactive ticking bomb in the Pacific Ocean.

More pollution news on Los Angeles Times, Strange Sounds and Steve Quayle.

I can remember the commercials on tv in the mid 60s, against DDT.

FIshed Catalina, Palos Verdes, and Santa Monic bay. One old fisherman told me to examine the organs of fish before you eat them. If tumors are visible, then discard.

PCB’s were the issue in the 80s.